Hamlet (1996)

DIRECTOR: Kenneth Branagh

CAST:

Kenneth Branagh, Sir Derek Jacobi, Julie Christie, Kate Winslet, Nicholas Farrell, Michael Maloney, Richard Briers, Charlton Heston, Billy Crystal, Robin Williams, Brian Blessed, Jack Lemmon, Rosemary Harris, Rufus Sewell, Timothy Spall, Reece Dinsdale, Gerard Depardieu, Sir John Gielgud, Judi Dench, Sir Richard Attenborough

REVIEW:

WARNING: This review mentions specific details of the plot

In the world of Shakespearean film, few figures loom larger than Kenneth Branagh. William Shakespeare is something of an obsession for Branagh, who directed Henry V and Much Ado About Nothing, co-starred in Othello, and here wears three hats as writer, director, and star of this lavish, star-studded adaptation of Hamlet, the only version to include every single line from the play intact and as such running approximately four hours. But even for those who find the prospect of wading through four hours of unadulterated Shakespearean dialogue intimidating, the sumptuous production values and high level of acting of Branagh’s adaptation should make it worth investing the time and effort for anyone interested in one of Shakespeare’s most famous tragedies.

While the dialogue turns some off to anything Shakespeare, it’s easy to see the appeal of Hamlet’s plot, which includes twists, turns, betrayals, revenge, love, madness (both real and faked), confrontations that drip with animosity and tension, and a climactic duel to the death, followed by the untimely demises of almost all of the remaining significant characters (it is a Shakespearean tragedy after all; the annihilation of most of the cast is to be expected). It has humor and grandeur and even some good old-fashioned swashbuckling adventure. The main storyline is a compelling one: young Prince Hamlet (Kenneth Branagh) is mourning the sudden death of his idolized father, King Hamlet (Brian Blessed) of Denmark, and feels deeply betrayed by his widowed mother Gertrude’s (Julie Christie) quick remarriage to his father’s brother Claudius (Derek Jacobi). The ghost of Hamlet’s father is haunting Elsinore Castle, and when Hamlet follows it into the forest, it reveals Claudius’ murder of the King to claim both the throne and the Queen for himself. Hamlet vows revenge, and thus begins his descent into obsession and madness (or a carefully orchestrated façade of insanity). Meanwhile, there are other peripheral issues that feed into the main plot. A group of traveling actors (including Charlton Heston and Rosemary Harris) has arrived to entertain at Elsinore Castle, and will play a key role in Hamlet’s plot to expose Claudius, two friends of Hamlet’s, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern (Timothy Spall and Reece Dinsdale) are sent by Claudius to spy on him, Ophelia (Kate Winslet), Hamlet’s lover and daughter of Claudius’ advisor Polonius (Richard Briers), is devastated by her father forbidding her to see him and Hamlet’s seeming insanity, and Fortinbras (Rufus Sewell), nephew to the King of Norway, is amassing an army to invade Denmark.

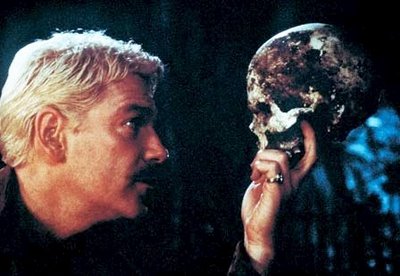

Hamlet features a somewhat unusual, and certainly eclectic cast. Kenneth Branagh and Sir Derek Jacobi come from Shakespearean backgrounds, but Kate Winslet, Charlton Heston, Billy Crystal, Robin Williams, Jack Lemmon, etc. aren’t typically associated with Shakespeare. What might be more surprising than some of the people who show up is that with only a couple minor exceptions, everyone does exceedingly well. Jack Lemmon is a little out-of-place (it’s a little hard to take him seriously saying famous Shakespearean lines like ‘something is rotten in the state of Denmark’), but his role is fairly small, and Robin Williams is, well, Robin Williams, but his bit consists of little more than a cameo near the end of the movie. Of the main cast members, screenwriter-director-star Kenneth Branagh is somewhat more impressive behind the camera than in front of it. Branagh loves grandiose, dramatic flourishes, and this works as a director, as he delights in creating grand spectacle, such as the ‘my thoughts be bloody’ soliloquy, in which the camera pans out from a black-clothed Hamlet standing as a solitary figure in a white expanse of snow, the Norwegian army in the distance behind him. Considering Branagh is directing as well as starring, it’s easy to say that he films himself rather grandly throughout, but it’s also grand filmmaking. Branagh shows a good, if unsubtle, visual sense for symbolism, both there and with the rain of white flower petals in the magnificent throne room during Claudius’ opening address to the court that only makes Hamlet in his black uniform stand out all the more strikingly, his dark clothing a visual representation of the seething resentment in his heart setting him apart from the celebratory court. As Hamlet, his performance mostly works, but I have a few nitpicks. First is physical, as Branagh is simply too old for college student Hamlet. Acting-wise, he chomps on the scenery with theatrical abandon. On the one hand, there’s something to be said for Branagh’s seemingly boundless energy, and his passion for Shakespeare is palpable, but his performance lacks subtlety. Branagh has a tendency to overact, and especially goes over-the-top when Hamlet is feigning insanity. Some of his lines would also have had more resonance if he had settled down enough to let himself breathe instead of blasting through full-throttle, dashing around Elsinore with gung-ho verve. However, his delivery of the “to be or not to be” soliloquy is cool and controlled, and he has a few scenes where the theatricality falls away and he cuts to the heart of Hamlet’s pain. A case could easily be made that the real standout is Sir Derek Jacobi, who gives a more subdued but masterful interpretation of Claudius, making him a somewhat complex and conflicted villain, yet still scheming and detestable enough to deserve his comeuppance. Jacobi’s Claudius is politically savvy-pay attention to the scene where Claudius is confronted by Polonius’ vengeful son Laertes (Michael Maloney), and how coolly and smoothly he turns Laertes’ anger away from himself and toward Hamlet-but he also seems to genuinely love Gertrude, and is privately tormented by his own guilty conscience. Jacobi had previously played Hamlet himself in several productions, and his command of the dialogue and the material is clear. Hamlet’s confrontations with Claudius, starting with thinly-veiled hostility that only gets more open as time wears on, crackle with tension. Julie Christie is a fine Gertrude, who seems oblivious to her husband’s plotting and the reason for her son’s anger with her, although she gets a little overwrought in her bedroom row with Hamlet. One of the best performances in the supporting cast is Kate Winslet, whose Ophelia is easily the most innocent victim in the story, and pours out her anguish like she tears it from her guts. Michael Maloney gives another intense and impassioned performance as her brother Laertes, and Nicholas Farrell is also strong as Hamlet’s faithful friend Horatio (along with Ophelia, about the only character who has the right to a completely clear conscience). Richard Briers brings a touch of more nuance and depth to the foolish Polonius than the character is sometimes granted; his judgment is off base at every turn, and he’s hopelessly in over-his-head when he tries to match wits with Hamlet, but Briers avoids making him a one-note fatuous caricature. In smaller roles we have Timothy Spall and Reece Dinsdale as the fawning Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, Rufus Sewell as Fortinbras (who only gets any substantial dialogue in the last five minutes or so), and Brian Blessed, bringing his commanding presence to the ghost of King Hamlet. There are small roles for Rosemary Harris (now best-known as Spider-Man’s Aunt May), and Gerard Depardieu, and even blink-and-you’ll-miss-it cameos from Sir John Gielgud (one of the Shakespearean actors), Dame Judi Dench, and Sir Richard Attenborough. Charlton Heston, not usually thought of in connection with Shakespeare, gives a powerful reading of the Player King’s soliloquy, and Billy Crystal surprisingly makes himself comfortably at home as the sardonic gravedigger. Overall, with only one or two weak spots, this is a solid ensemble.

Hamlet features a somewhat unusual, and certainly eclectic cast. Kenneth Branagh and Sir Derek Jacobi come from Shakespearean backgrounds, but Kate Winslet, Charlton Heston, Billy Crystal, Robin Williams, Jack Lemmon, etc. aren’t typically associated with Shakespeare. What might be more surprising than some of the people who show up is that with only a couple minor exceptions, everyone does exceedingly well. Jack Lemmon is a little out-of-place (it’s a little hard to take him seriously saying famous Shakespearean lines like ‘something is rotten in the state of Denmark’), but his role is fairly small, and Robin Williams is, well, Robin Williams, but his bit consists of little more than a cameo near the end of the movie. Of the main cast members, screenwriter-director-star Kenneth Branagh is somewhat more impressive behind the camera than in front of it. Branagh loves grandiose, dramatic flourishes, and this works as a director, as he delights in creating grand spectacle, such as the ‘my thoughts be bloody’ soliloquy, in which the camera pans out from a black-clothed Hamlet standing as a solitary figure in a white expanse of snow, the Norwegian army in the distance behind him. Considering Branagh is directing as well as starring, it’s easy to say that he films himself rather grandly throughout, but it’s also grand filmmaking. Branagh shows a good, if unsubtle, visual sense for symbolism, both there and with the rain of white flower petals in the magnificent throne room during Claudius’ opening address to the court that only makes Hamlet in his black uniform stand out all the more strikingly, his dark clothing a visual representation of the seething resentment in his heart setting him apart from the celebratory court. As Hamlet, his performance mostly works, but I have a few nitpicks. First is physical, as Branagh is simply too old for college student Hamlet. Acting-wise, he chomps on the scenery with theatrical abandon. On the one hand, there’s something to be said for Branagh’s seemingly boundless energy, and his passion for Shakespeare is palpable, but his performance lacks subtlety. Branagh has a tendency to overact, and especially goes over-the-top when Hamlet is feigning insanity. Some of his lines would also have had more resonance if he had settled down enough to let himself breathe instead of blasting through full-throttle, dashing around Elsinore with gung-ho verve. However, his delivery of the “to be or not to be” soliloquy is cool and controlled, and he has a few scenes where the theatricality falls away and he cuts to the heart of Hamlet’s pain. A case could easily be made that the real standout is Sir Derek Jacobi, who gives a more subdued but masterful interpretation of Claudius, making him a somewhat complex and conflicted villain, yet still scheming and detestable enough to deserve his comeuppance. Jacobi’s Claudius is politically savvy-pay attention to the scene where Claudius is confronted by Polonius’ vengeful son Laertes (Michael Maloney), and how coolly and smoothly he turns Laertes’ anger away from himself and toward Hamlet-but he also seems to genuinely love Gertrude, and is privately tormented by his own guilty conscience. Jacobi had previously played Hamlet himself in several productions, and his command of the dialogue and the material is clear. Hamlet’s confrontations with Claudius, starting with thinly-veiled hostility that only gets more open as time wears on, crackle with tension. Julie Christie is a fine Gertrude, who seems oblivious to her husband’s plotting and the reason for her son’s anger with her, although she gets a little overwrought in her bedroom row with Hamlet. One of the best performances in the supporting cast is Kate Winslet, whose Ophelia is easily the most innocent victim in the story, and pours out her anguish like she tears it from her guts. Michael Maloney gives another intense and impassioned performance as her brother Laertes, and Nicholas Farrell is also strong as Hamlet’s faithful friend Horatio (along with Ophelia, about the only character who has the right to a completely clear conscience). Richard Briers brings a touch of more nuance and depth to the foolish Polonius than the character is sometimes granted; his judgment is off base at every turn, and he’s hopelessly in over-his-head when he tries to match wits with Hamlet, but Briers avoids making him a one-note fatuous caricature. In smaller roles we have Timothy Spall and Reece Dinsdale as the fawning Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, Rufus Sewell as Fortinbras (who only gets any substantial dialogue in the last five minutes or so), and Brian Blessed, bringing his commanding presence to the ghost of King Hamlet. There are small roles for Rosemary Harris (now best-known as Spider-Man’s Aunt May), and Gerard Depardieu, and even blink-and-you’ll-miss-it cameos from Sir John Gielgud (one of the Shakespearean actors), Dame Judi Dench, and Sir Richard Attenborough. Charlton Heston, not usually thought of in connection with Shakespeare, gives a powerful reading of the Player King’s soliloquy, and Billy Crystal surprisingly makes himself comfortably at home as the sardonic gravedigger. Overall, with only one or two weak spots, this is a solid ensemble.

There are a lot of interesting things about Hamlet, plenty of which aren’t related to the main plotline, and some of which appears only in subtext. The characters of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are members of a series of negative, two-faced depictions of Jews in Shakespearean plays (their Judaism is not explicitly mentioned, but their names make it apparent) including the greedy, conniving villain Shylock in The Merchant of Venice (though the line is sometimes left out in modern adaptations, the ingredients for the witches’ brew in Macbeth includes ‘liver of blaspheming Jew’). There is also room for some ambiguity about whether Hamlet’s relationship with Horatio strays beyond the realm of conventional friendship (just as there has long been speculation about the sexual orientation of Shakespeare himself). Branagh holds to the Bard’s words with unwavering fidelity, but adds the touch of visualizing some of the events only discussed in dialogue, such as showing us Claudius’ poisoning of his brother, Hamlet and Ophelia in bed, and a flashback to Hamlet’s youth of tranquility and leisure, with he and his parents enjoying games and the entertainment of court jester Yorick. Not only do these visual touches help casual viewers grasp what’s being discussed, they also give the dialogue more weight and meaning–seeing glimpses of Ophelia’s blissful stolen moments with Hamlet makes it mean more when she is cast out of his existence, and Claudius looks increasingly horrified as he watches his brother in his death throes. While most productions completely omit the character of Fortinbras due to time constraints, his inclusion here adds yet another layer of symbolism. Fortinbras may be a minor role, screentime-wise, but his story (the vengeful son of the Norwegian King slain by King Hamlet in battle, returning to claim Denmark in revenge) parallels Hamlet’s, and shows the thought Shakespeare put into even seemingly minor peripheral characters. The play is usually portrayed in a dark, dim castle, but Branagh’s version is sumptuous and brightly-lit, highlighting the lavishness of the characters’ environment and surroundings, using rooms filled with mirrors to convey the play’s themes of espionage and suspicion. Hamlet includes some of the most famous lines in Shakespearean literature, including ‘something is rotten in the state of Denmark’, ‘the lady doth protest too much’, ‘murder most foul’, ‘to thine own self be true’, ‘brevity is the soul of wit’, ‘there are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy, Horatio’s farewell to Hamlet ‘farewell, sweet prince’, and, of course, ‘to be or not to be, that is the question’. While watching Hamlet one realizes how many familiar sayings stem from Shakespeare; the title of the film What Dreams May Come comes from the ‘to be or not to be’ soliloquy. There are some witty insults, most coming from Hamlet, with among the most memorable describing Rosencrantz and Guildenstern as ‘friends whom I trust as I would adders fanged’ and his description of Claudius as ‘a little more than kin but less than kind’. Claudius himself remarks that ‘when sorrows come they come not single spies but in battalions’, and Hamlet admits ‘I could accuse me of such things that it were better had my mother not borne me’.

There are a lot of interesting things about Hamlet, plenty of which aren’t related to the main plotline, and some of which appears only in subtext. The characters of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are members of a series of negative, two-faced depictions of Jews in Shakespearean plays (their Judaism is not explicitly mentioned, but their names make it apparent) including the greedy, conniving villain Shylock in The Merchant of Venice (though the line is sometimes left out in modern adaptations, the ingredients for the witches’ brew in Macbeth includes ‘liver of blaspheming Jew’). There is also room for some ambiguity about whether Hamlet’s relationship with Horatio strays beyond the realm of conventional friendship (just as there has long been speculation about the sexual orientation of Shakespeare himself). Branagh holds to the Bard’s words with unwavering fidelity, but adds the touch of visualizing some of the events only discussed in dialogue, such as showing us Claudius’ poisoning of his brother, Hamlet and Ophelia in bed, and a flashback to Hamlet’s youth of tranquility and leisure, with he and his parents enjoying games and the entertainment of court jester Yorick. Not only do these visual touches help casual viewers grasp what’s being discussed, they also give the dialogue more weight and meaning–seeing glimpses of Ophelia’s blissful stolen moments with Hamlet makes it mean more when she is cast out of his existence, and Claudius looks increasingly horrified as he watches his brother in his death throes. While most productions completely omit the character of Fortinbras due to time constraints, his inclusion here adds yet another layer of symbolism. Fortinbras may be a minor role, screentime-wise, but his story (the vengeful son of the Norwegian King slain by King Hamlet in battle, returning to claim Denmark in revenge) parallels Hamlet’s, and shows the thought Shakespeare put into even seemingly minor peripheral characters. The play is usually portrayed in a dark, dim castle, but Branagh’s version is sumptuous and brightly-lit, highlighting the lavishness of the characters’ environment and surroundings, using rooms filled with mirrors to convey the play’s themes of espionage and suspicion. Hamlet includes some of the most famous lines in Shakespearean literature, including ‘something is rotten in the state of Denmark’, ‘the lady doth protest too much’, ‘murder most foul’, ‘to thine own self be true’, ‘brevity is the soul of wit’, ‘there are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy, Horatio’s farewell to Hamlet ‘farewell, sweet prince’, and, of course, ‘to be or not to be, that is the question’. While watching Hamlet one realizes how many familiar sayings stem from Shakespeare; the title of the film What Dreams May Come comes from the ‘to be or not to be’ soliloquy. There are some witty insults, most coming from Hamlet, with among the most memorable describing Rosencrantz and Guildenstern as ‘friends whom I trust as I would adders fanged’ and his description of Claudius as ‘a little more than kin but less than kind’. Claudius himself remarks that ‘when sorrows come they come not single spies but in battalions’, and Hamlet admits ‘I could accuse me of such things that it were better had my mother not borne me’.

Hamlet contains any number of memorable scenes, starting with the wedding celebration in the throne room. Then there is the performance of the play put on by the visiting actors, which Hamlet has written and devised as a thinly (very thinly) veiled reenactment of Claudius’ poisoning of his father. As the play goes on, the audience members begin glancing at each other and at Claudius, and the tension builds to a memorable pitch until Claudius, seeing his crime flash before his eyes, abruptly shoots to his feet, playing into Hamlet’s hands with his revealing reaction. The play also stirs Claudius’ guilty conscience, which leads us into the next memorable scene as Claudius releases his private conflict in an empty confession box, unaware that Hamlet is hiding in the priest’s box beside him, visualizing driving his knife through his father’s murderer’s ear. He stops himself because he worries that murdering Claudius while he confesses his sins will allow him to die with a clean slate and enter Heaven, and that he must bide his time and strike Claudius down without giving him the chance of confession or forgiveness (this brings back a recurring religious theme, as the Ghost laments that he was murdered without the chance to confess his sins and died ‘with all my imperfections on my head’, dooming his spirit to wander the Earth ‘until all my sins are burnt and purged away’). Best of all is the climactic duel, which is suitably exciting and swashbuckling, with a nod to Errol Flynn, and ends with the quick succession of deaths, some tragic, some deserved, some simply unfortunate, that is a staple of Shakespearean tragedies.

Hamlet contains any number of memorable scenes, starting with the wedding celebration in the throne room. Then there is the performance of the play put on by the visiting actors, which Hamlet has written and devised as a thinly (very thinly) veiled reenactment of Claudius’ poisoning of his father. As the play goes on, the audience members begin glancing at each other and at Claudius, and the tension builds to a memorable pitch until Claudius, seeing his crime flash before his eyes, abruptly shoots to his feet, playing into Hamlet’s hands with his revealing reaction. The play also stirs Claudius’ guilty conscience, which leads us into the next memorable scene as Claudius releases his private conflict in an empty confession box, unaware that Hamlet is hiding in the priest’s box beside him, visualizing driving his knife through his father’s murderer’s ear. He stops himself because he worries that murdering Claudius while he confesses his sins will allow him to die with a clean slate and enter Heaven, and that he must bide his time and strike Claudius down without giving him the chance of confession or forgiveness (this brings back a recurring religious theme, as the Ghost laments that he was murdered without the chance to confess his sins and died ‘with all my imperfections on my head’, dooming his spirit to wander the Earth ‘until all my sins are burnt and purged away’). Best of all is the climactic duel, which is suitably exciting and swashbuckling, with a nod to Errol Flynn, and ends with the quick succession of deaths, some tragic, some deserved, some simply unfortunate, that is a staple of Shakespearean tragedies.

The Shakespearean dialogue is the most significant issue for many non-Shakespeare aficionados (including myself) attempting to watch and enjoy something like Hamlet. Certainly it can be a challenge to understand, and some nuances and passages of dialogue may be lost on casual viewers, but the plot is clear and easy enough to follow that anyone should be able to get the gist, if not every detail, and the story is a good one. And even if one has difficulty understanding everything that’s being said in Hamlet, it’s impossible not to appreciate the sumptuous lavishness of the production values. Between the magnificent grandeur of Elsinore Castle, the wintry plain beyond its walls, and the elegance and attention to detail of the characters’ wardrobes, Hamlet is a non-stop visual feast for the eyes. And none of the characters are one-dimensional. Hamlet, like most Shakespearean tragic heroes, is entirely too complex for his own good, driven by a raging storm of passions and powerful emotions, driven to the point of obsession to avenge his father by destroying his uncle, and also wrestling with his his feelings of being betrayed and abandoned by his mother. While his crusade for revenge of his father’s murder seems righteous, he treats the virtuous Ophelia cruelly, painting her and every other woman with the same faults he ascribes to his mother (‘frailty, thy name is woman!’). Meanwhile, Ophelia is a side casualty of the main plot, which drives her to despair, then finally to complete insanity and ultimately suicide. Claudius has committed ‘murder most foul’, poisoning his brother to have his throne and his wife, but Jacobi plays him as a torn and conflicted character rather than a one-dimensional villain.

As far as film goes, Kenneth Branagh’s name is nearly intertwined with William Shakespeare’s, and his version of Hamlet lives up to any expectations. Widely-considered the best (and the most faithful) adaptation of the play ever to be brought to the screen, it’s a must-see for any Shakespeare buff (though by no means does one need to be an aficionado to enjoy it for its sheer drama and epic spectacle), and one of Branagh’s crowning achievements.

***1/2