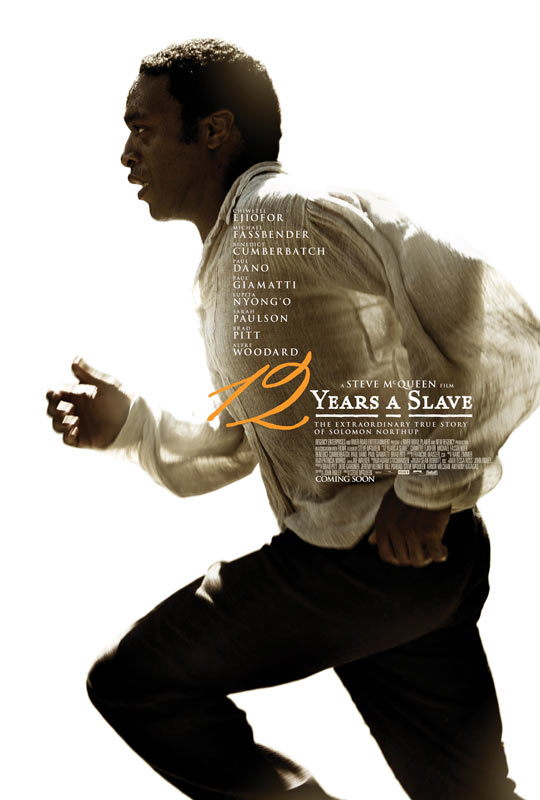

12 Years a Slave (2013)

DIRECTOR: Steve McQueen

CAST: Chiwetel Ejiofor, Michael Fassbender, Lupita Nyong’o, Benedict Cumberbatch, Sarah Paulson, Brad Pitt, Paul Dano, Alfre Woodard, Paul Giamatti

REVIEW:

A powerful and haunting film and a stirring and important historical document, 12 Years a Slave may do for American slavery what Schindler’s List did for the Holocaust, using one man’s true story to portray the incalculable horrors of an evil system. While this film does not quite match the power of Steven Spielberg’s epic, it brings the grim, stark realities of slavery home in ways that are hard-hitting and eye-opening. Nothing is sugarcoated—nor should it be—and there are moments of jarring brutality depicted unflinchingly to the point of being difficult to watch.

A powerful and haunting film and a stirring and important historical document, 12 Years a Slave may do for American slavery what Schindler’s List did for the Holocaust, using one man’s true story to portray the incalculable horrors of an evil system. While this film does not quite match the power of Steven Spielberg’s epic, it brings the grim, stark realities of slavery home in ways that are hard-hitting and eye-opening. Nothing is sugarcoated—nor should it be—and there are moments of jarring brutality depicted unflinchingly to the point of being difficult to watch.

In 1840s New York, Solomon Northup (Chiwetel Ejiofor) is a born-and-raised free man who has never tasted slavery, a man of culture and education and an expert violinist who lives with his wife and young children. Solomon’s fortunes take an abrupt and extreme downturn when he is tricked into accompanying two men who get him drunk or possibly poisoned, kidnap him, and sell him into slavery in Georgia. At first, the bewildered Solomon indignantly demands his release, but his protests are in vain, and he endures a degrading slave auction overseen by Theophilius Freeman (Paul Giamatti), who sells him to minister William Ford (Benedict Cumberbatch). Ford recognizes and appreciates Solomon’s intelligence and education and treats him kindly—including gifting him a violin—but Solomon’s time with Ford is tainted by a conflict with his bullying overseer Tibeats (Paul Dano). This, and Ford’s debts, eventually land Solomon in the hands of Edwin Epps (Michael Fassbender), an alcoholic, Bible-thumping, erratic man who subjects his slaves to wild mood swings and capricious whims that can run anywhere from impromptu dancing to bursts of rage. Other key figures on the Epps plantation are slave Patsy (Lupita Nyong’o), the object of Epps’ sexual obsession, and Epps’ icy wife (Sarah Paulson), whose bitter jealousy of Patsy brings out a cruelty and viciousness equal to the worst her husband is capable of. Meanwhile, Solomon struggles to maintain his own dignity and identity, until a chance encounter with a Canadian abolitionist (Brad Pitt) could bring a spark of hope.

While John Ridley’s screenplay both condenses and adds a smidgeon of dramatic license, it stays closer to the facts than many movies boasting a “based on a true story” tagline, and overall is a faithful adaptation of Solomon Northup’s memoirs. In particular, some parts that might seem exaggerated—the loathsomeness of both Mr. and Mrs. Epps—are often virtually word-for-word from Northup’s account. There is little if any Hollywood overdramatizing, no heroism, no comeuppance for the film’s “villains”, and apart from a tussle in a field with Solomon giving the bullying Tibeats a taste of his own medicine, no moments to get audiences cheering. Not every white character is vile, and not every slave is noble. 12 Years a Slave is a bleak, grim journey that sometimes has almost the feel of a horror movie as we follow Solomon on his nightmarish odyssey. Director Steve McQueen (no relation to the late actor) pulls no punches. There is full frontal nudity, both male and female, scattered casually around, and one whipping scene late in the film that rivals The Passion for how graphically it portrays the shredded flesh that results. There is no downplaying the effects of a whipping here. Gasps were audible in my theater at the unsparing close-up of the victim’s mutilated back, and various other scenes were obviously tough for some audience members to take. That, more than anything else in my opinion, means 12 Years a Slave is doing its job. But equally disturbing are lower-key, less violent moments, such as when a woman essentially forces herself on Solomon, using him to bring herself to orgasm in a moment of bliss, then resuming her quiet sobbing as the grimness of her reality returns. We see a hysterically screaming mother pried apart from her children as all are sold to different plantations, a slave drop dead from heat while picking cotton and being casually buried, and in a memorably disturbing scene, Solomon hanging from a tree, struggling to keep from strangling to death, for agonizingly long minutes while other slaves, too fearful or too resigned to intervene or even look in his direction, go quietly about their chores in the background and ignore him. Even kinder masters and mistresses, such as Mrs. Ford, display jarring ignorance, such as when she attempts to comfort the devastated mother with the shockingly unhelpful assurance that “your children will soon be forgotten”, showing that even slaveowners who treated their slaves better than most do not fully recognize their slave’s humanity. 12 Years a Slave is full of moments like these that add up into conveying the sheer dehumanizing degrading effects that slavery had on its victims. And the movie also argues that the victims weren’t the only ones it damaged. The movie touches on a tricky question that could have borne more in depth examination: can someone simultaneously be both a slave-owner and a good person? Solomon insists, both in his memoirs and onscreen, that Benedict Cumberbatch’s Ford is a good man “under the circumstances”, but that might be a key qualifier. Ford treats Solomon to various small kindnesses, but when Solomon tries to tell his master of his real background, Ford refuses to hear it, putting his debts ahead of the knowledge that he has a rightfully free man in his possession, showing that even a man with a sense of decency is hamstrung and morally compromised by his participation in an abhorrent system. I wouldn’t have minded Cumberbatch’s contradictory Ford having more screentime instead of being quickly shuffled aside to make way for more black-and-white characters like Fassbender’s abusive Epps and Brad Pitt’s virtuous Bass.

While John Ridley’s screenplay both condenses and adds a smidgeon of dramatic license, it stays closer to the facts than many movies boasting a “based on a true story” tagline, and overall is a faithful adaptation of Solomon Northup’s memoirs. In particular, some parts that might seem exaggerated—the loathsomeness of both Mr. and Mrs. Epps—are often virtually word-for-word from Northup’s account. There is little if any Hollywood overdramatizing, no heroism, no comeuppance for the film’s “villains”, and apart from a tussle in a field with Solomon giving the bullying Tibeats a taste of his own medicine, no moments to get audiences cheering. Not every white character is vile, and not every slave is noble. 12 Years a Slave is a bleak, grim journey that sometimes has almost the feel of a horror movie as we follow Solomon on his nightmarish odyssey. Director Steve McQueen (no relation to the late actor) pulls no punches. There is full frontal nudity, both male and female, scattered casually around, and one whipping scene late in the film that rivals The Passion for how graphically it portrays the shredded flesh that results. There is no downplaying the effects of a whipping here. Gasps were audible in my theater at the unsparing close-up of the victim’s mutilated back, and various other scenes were obviously tough for some audience members to take. That, more than anything else in my opinion, means 12 Years a Slave is doing its job. But equally disturbing are lower-key, less violent moments, such as when a woman essentially forces herself on Solomon, using him to bring herself to orgasm in a moment of bliss, then resuming her quiet sobbing as the grimness of her reality returns. We see a hysterically screaming mother pried apart from her children as all are sold to different plantations, a slave drop dead from heat while picking cotton and being casually buried, and in a memorably disturbing scene, Solomon hanging from a tree, struggling to keep from strangling to death, for agonizingly long minutes while other slaves, too fearful or too resigned to intervene or even look in his direction, go quietly about their chores in the background and ignore him. Even kinder masters and mistresses, such as Mrs. Ford, display jarring ignorance, such as when she attempts to comfort the devastated mother with the shockingly unhelpful assurance that “your children will soon be forgotten”, showing that even slaveowners who treated their slaves better than most do not fully recognize their slave’s humanity. 12 Years a Slave is full of moments like these that add up into conveying the sheer dehumanizing degrading effects that slavery had on its victims. And the movie also argues that the victims weren’t the only ones it damaged. The movie touches on a tricky question that could have borne more in depth examination: can someone simultaneously be both a slave-owner and a good person? Solomon insists, both in his memoirs and onscreen, that Benedict Cumberbatch’s Ford is a good man “under the circumstances”, but that might be a key qualifier. Ford treats Solomon to various small kindnesses, but when Solomon tries to tell his master of his real background, Ford refuses to hear it, putting his debts ahead of the knowledge that he has a rightfully free man in his possession, showing that even a man with a sense of decency is hamstrung and morally compromised by his participation in an abhorrent system. I wouldn’t have minded Cumberbatch’s contradictory Ford having more screentime instead of being quickly shuffled aside to make way for more black-and-white characters like Fassbender’s abusive Epps and Brad Pitt’s virtuous Bass.

The movie belongs to Chiwetel Ejiofor, who may well find himself an Oscar nominee for his performance here. Guest stars come and go as Solomon changes hands and plantations, but he is the only constant. The supporting cast revolves around him, and no one else’s screentime is near his. Michael Fassbender and Lupita Nyong’o, probably the most significant supporting characters, don’t show up until the movie is halfway over. Paul Giamatti and Alfre Woodard basically have cameos, and Brad Pitt only slightly more. Benedict Cumberbatch, Sarah Paulson, and Paul Dano have a few scenes apiece. Like director McQueen, Ejiofor is a black British man (adopting an American accent here). Ejiofor never goes for overacting or melodrama. His performance is low-key and subdued and invests Solomon with a quiet dignity and occasional bursts of defiance. Ejiofor unerringly plays Solomon’s comfortable life before his abduction (in which he did not give a second glance to slaves on the street), his initial naïve determination that this is a terrible misunderstanding that will be quickly sorted out, his stoic endurance, and his growing despair.

Michael Fassbender (who previously starred for McQueen in Hunger and Shame) plays Edwin Epps something like what Schindler’s List‘s Amon Goeth might have been like as a Southern plantation owner. Like Goeth, he is unpredictable and unstable, and like Goeth, he is tormented by his sexual fixation with a member of a race he views as subhuman. The almost climactic scene in which Epps forces Solomon to whip Patsy is 12 Years a Slave at its most wrenching. Lupita Nyong’o, a Kenyan actress in her American film debut, is painfully convincing as Patsy, who must endure simultaneously being the target of Epps’ sexual obsession and his wife’s jealous abuse. Oscars have been handed out for lesser performances than various ones on display here. The rest of the characters don’t get as much focus. Benedict Cumberbatch and Sarah Paulson make as much of Ford and Mrs. Epps as their limited screentime allows, Cumberbatch as a torn man of contradictions I wouldn’t have minded seeing more of, and Paulson making Mrs. Epps as or possibly more detestable than her husband. Paul Giamatti (as the slimy slave auctioneer Freeman) and Alfre Woodard (as a slave treated as the “wife” of a neighboring plantation owner who enjoys a cushy life) have basically cameos. Only two cast members strike slightly “off” notes. First is Paul Dano as the petty bullying brat Tibeats. I’m not sure if it’s the character or Dano, but Tibeats comes off as over-the-top. Brad Pitt, who has a surprisingly small role late in the film, is a little distracting when he pops up, and it comes off like Pitt, who produced, inserting himself into the movie when he should have stayed behind-the-scenes. While most of the cast is made up of character actors like Chiwetel Ejiofor, Michael Fassbender, Benedict Cumberbatch, Paul Dano, etc., who are neither unknowns nor superstars, Pitt is just too “big” to avoid calling undue attention to himself; when he shows up, we see Brad Pitt, not Mr. Bass. It’s a minor quibble, but one worth mentioning.

Michael Fassbender (who previously starred for McQueen in Hunger and Shame) plays Edwin Epps something like what Schindler’s List‘s Amon Goeth might have been like as a Southern plantation owner. Like Goeth, he is unpredictable and unstable, and like Goeth, he is tormented by his sexual fixation with a member of a race he views as subhuman. The almost climactic scene in which Epps forces Solomon to whip Patsy is 12 Years a Slave at its most wrenching. Lupita Nyong’o, a Kenyan actress in her American film debut, is painfully convincing as Patsy, who must endure simultaneously being the target of Epps’ sexual obsession and his wife’s jealous abuse. Oscars have been handed out for lesser performances than various ones on display here. The rest of the characters don’t get as much focus. Benedict Cumberbatch and Sarah Paulson make as much of Ford and Mrs. Epps as their limited screentime allows, Cumberbatch as a torn man of contradictions I wouldn’t have minded seeing more of, and Paulson making Mrs. Epps as or possibly more detestable than her husband. Paul Giamatti (as the slimy slave auctioneer Freeman) and Alfre Woodard (as a slave treated as the “wife” of a neighboring plantation owner who enjoys a cushy life) have basically cameos. Only two cast members strike slightly “off” notes. First is Paul Dano as the petty bullying brat Tibeats. I’m not sure if it’s the character or Dano, but Tibeats comes off as over-the-top. Brad Pitt, who has a surprisingly small role late in the film, is a little distracting when he pops up, and it comes off like Pitt, who produced, inserting himself into the movie when he should have stayed behind-the-scenes. While most of the cast is made up of character actors like Chiwetel Ejiofor, Michael Fassbender, Benedict Cumberbatch, Paul Dano, etc., who are neither unknowns nor superstars, Pitt is just too “big” to avoid calling undue attention to himself; when he shows up, we see Brad Pitt, not Mr. Bass. It’s a minor quibble, but one worth mentioning.

There are other, minor issues. The early scene of a slave woman using Solomon to pleasure herself, while giving insight into her mental state, feels gratuitous. The titular twelve years pass awfully quickly, with the script condensing the passage of time. The flashbacks are occasionally a little confusing; fortunately, there aren’t many. While there’s nothing wrong with the acting of Michael Fassbender or Benedict Cumberbatch, both struggle with Southern accents. While Hans Zimmer’s score is generally effective (albeit sometimes regurgitating his work from Inception and Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy), there is one scene in particular where he calls a distracting amount of attention to himself.

But compared to the impact made by myriad scenes, the few small flaws of 12 Years a Slave fall by the wayside. This is an important movie that, as difficult as some parts may be, ought to be seen. It is not a feel-good or uplifting viewing, but it is a worthwhile one.

* * * 1/2