Oppenheimer (2023)

DIRECTOR: Christopher Nolan

CAST: Cillian Murphy, Matt Damon, Emily Blunt, Robert Downey Jr., Florence Pugh

REVIEW:

Ambitious director Christopher Nolan has called Oppenheimer—-a biopic of the “father of the atom bomb”, American theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, largely working off the book American Prometheus by Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin—-his most challenging project to date, but while its ambition and technical accomplishments are admirable, Oppenheimer like Interstellar and Dunkirk before it also falls victim to some of Nolan’s increasingly self-indulgent less admirable qualities. There are any number of flashes of greatness and strong moments and performances in the mix, and moments that are unsettling, poignant, and thought-provoking, but Oppenheimer is not all that it could have been.

Rather than following a straightforward linear narrative biopic structure, Oppenheimer bounces around restlessly (and sometimes disorientingly) between a few time periods. In one, we sketch out the rise of neurotic but brilliant theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) as he attends prestigious universities in both the United States and Europe, rubbing shoulders with luminaries like Albert Einstein (Tom Conti), Niels Bohr (Kenneth Branagh), and Werner Heisenberg (Matthias Schweighöfer), among many others, and starts to formulate the theories that will eventually lead to the development of the atom bomb. During this time, Oppenheimer has personal associations that will come back to bite him later, including dabbling in Communist Party meetings and having an affair with an unstable Party member, Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh). Another plotline takes place in the post-war 1950s, where Oppenheimer is dragged in front of a hearing, butting heads with a smarmy prosecutor (Jason Clarke) while his politics, affairs, and friendships are sifted through with a fine-toothed comb while deciding the renewal of his security clearance, along with insinuations of having been careless about security during the Manhattan Project and possible ties to the Soviet Union. Though he doesn’t yet realize it, the hearing is a kangaroo court with a predetermined outcome, all part of a concerted campaign to destroy his reputation, orchestrated by his onetime friend Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.). And in between, of course, is his involvement in the Manhattan Project where, under the supervision of General Leslie Groves (Matt Damon) and with an army of scientists at his disposal, Oppenheimer works feverishly to build and successfully detonate an atomic bomb before the Nazis. It’s not much of a spoiler that he succeeds, but Oppenheimer will spend the rest of his life being haunted by the death and destruction he has helped unleash.

Like Dunkirk, Oppenheimer showcases both Nolan’s strengths and his less admirable qualities as a director. Unfortunately, a growing self-indulgence that became problematic in Interstellar continues here. Nolan’s fondness for non-linear chronologies is in full effect, along with excessive stylistic flourishes creeping in, including most of Robert Downey Jr.’s scenes filmed in black-and-white (possibly to delineate the different time period), Oppenheimer periodically zoning out into imagining kaleidoscopic imagery, exploding atoms, and black holes, and conversations being drowned out by imagined percussive drumming and the white flash of an atomic blast, flourishes meant to convey the central character’s mind but often more excessive and distracting than effective. This is in addition to Ludwig Goransson’s pounding percussive score, which occasionally drowns out dialogue (Goransson has seemingly replaced Hans Zimmer as Nolan’s go-to composer, but his occasionally overbearing thunderous style is in the same vein). The non-linear chronology is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, the unconventional narrative structure sets Oppenheimer apart from generic “Point A to Point B” biopics. There are times when events come full circle satisfyingly (Robert Downey Jr’s subplot, which takes up quite a bit of screentime, feels superfluous for a while until finally coming to a head in dramatically effective fashion in the climax), and others, especially early on, when all the jumping around is disorienting and hard to follow and holds us back from finding any character who’s well-established enough to care about except for Oppenheimer, and sometimes even him. The narrative often feels fragmented, and some events and character relationships feel skimmed through, even in a formidable three hour runtime with uneven pacing. In particular, Oppenheimer’s relationships with both his long-suffering wife Kitty (Emily Blunt) and his unstable on-again off-again mistress Jean Tatlock feel underdeveloped. In fact, there’s arguably more chemistry in the banter between Cillian Murphy and Matt Damon (though their dynamic never gets enough emphasis to rise to the level of a “buddy movie”) than there is between either Murphy and Blunt or Murphy and Pugh, despite Nolan featuring the first graphic sex scenes of his career (Pugh and Murphy casually display nudity several times). While the tone is expectedly somber, as one would expect from both the subject matter and Nolan’s filmography, the movie is not completely devoid of a little low-key humor, even of the dark gallows variety, such as when Oppenheimer is forced to admit to Damon’s General Groves that there is a “near zero” possibility that the atomic test could destroy the world (“zero would be nice”, Damon quips).

Helping counterbalance Oppenheimer’s weaknesses is the strength of individual scenes and moments. The movie delves into interesting thematic questions, such as how much moral responsibility a creator bears for the ways in which his creation is used. Initially viewing his work purely in academic theoretical terms, Oppenheimer is seduced by his ambitions to perform a “miracle”, and tells both himself and subordinates with misgivings that what is done with their creation afterwards is not their concern or responsibility. Shellshocked by witnessing the first test, and haunted by the death and destruction wrought on Hiroshima and Nagasaki (which is left offscreen but briefly described to a horrified Oppenheimer) and the prospect of future global annihilation, he later pivots into becoming an impassioned advocate against nuclear proliferation, trying to use his influential position and heroic public image to influence government policy and head off an ever-escalating arms race with the Soviet Union, an act which runs him afoul of his old friend and Atomic Energy Commission Chairman Lewis Strauss, who sets out to railroad his career by dragging his reputation through the mud. Oppenheimer’s iconic “I have become Death…the destroyer of worlds” line is included, but more poignant are two later moments, one in which he responds unenthusiastically to the praise lavished on him by President Truman (Gary Oldman) and makes a haunted confession of feeling blood on his hands, and the final closing line in which he finally understands a long-ago warning by his old friend Albert Einstein.

As is to be expected from any Nolan movie, even his most flawed ones, Oppenheimer is ambitious and impressively technically accomplished. Hoyte Van Hoytema’s sweeping wide shots of the New Mexican desert recall old classic films like Gandhi, Patton, and Lawrence of Arabia (themselves large-scale biopics of famous—-and controversial—-historical figures). The movie’s centerpiece, unsurprisingly, is the Trinity atomic bomb test in the New Mexican desert, where Nolan builds up the suspense for about twenty minutes leading up to it, and then lets it unfold in a historically accurate but unconventional fashion. Always scorning excessive CGI, Nolan has claimed there are no CGI shots in the movie, preferring to rely on practical effects. The Trinity explosion was created practically, with a hybrid of gasoline, propane, aluminum, and magnesium, filmed at high speeds from different angles and then digitally layered together to create the iconic mushroom cloud (it’s worth noting that the atom bomb tested at Los Alamos was small-scale by later standards). In order for the black-and-white scenes to be shot in the same quality as the rest of the movie, Nolan employed Kodak to develop the first ever black-and-white film stock for iMax, continuing Nolan’s trend of being among an elite few directors (James Cameron being another) who continuously advance filmmaking technologies with each installment.

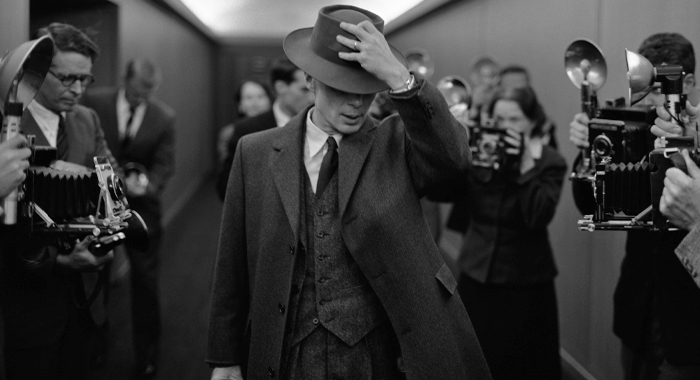

While Nolan has stocked Oppenheimer with a star-studded cast (probably most prominently Matt Damon and Robert Downey Jr.), the lead role went to arguably one of its lower-profile names. Cillian Murphy isn’t a newcomer or an unknown (he had his breakout role with 28 Days Later over twenty years ago, and is also something of a Nolan regular, having previously appeared in his Dark Knight trilogy, Inception, and Dunkirk), but he’s more a character actor than an A-lister (in fact, in recent years he’s probably been better-known for the gangster series Peaky Blinders than for his film roles). The casting works; with his intense piercing gaze and gaunt physique, Murphy looks the part of the haunted tortured genius, building Oppenheimer into a semi-tragic figure of almost Shakespearean proportions, a man who devotes his existence to a creation that he later spends the rest of his life being tormented by misgivings about. It’s a warts-and-all portrayal that doesn’t try to make Oppenheimer more likable or more accessible than he was. He is cold, aloof, obsessive, makes some careless decisions in his personal life, and is an unfaithful husband who both cheats on his own wife and has affairs with the wives of other men, even one he considers a friend. A more conventional “leading man” type actor might have wanted to look more “likable” in the lead role, but Murphy doesn’t shy away from imbuing Oppenheimer with an edgy intensity. Insofar as we sympathize with him, it’s because of the strength of Murphy’s performance and the way in which Oppenheimer’s career is eventually unfairly railroaded thanks to the machinations of a petty and spiteful man (if it’s a warts-and-all depiction of Oppenheimer, Lewis Strauss would be unlikely to enjoy the unflattering portrayal of himself).

It’s telling of Nolan’s clout in Hollywood that he can seemingly cast pretty much whoever he wants for what in many cases are small roles (Oscar winner Rami Malek, for example, does nothing but hold a clipboard until finally getting a “moment” near the end). Oppenheimer features some “big names”, but they’re in unglamorous supporting parts that don’t steal any spotlight from Murphy. Matt Damon, looking paunchy and sporting a mustache and far removed from Jason Bourne, plays the “straight man”of General Leslie Groves who immediately establishes a give-and-take banter with Murphy’s eccentric Oppenheimer. Nolan has rarely been known for writing strong female parts, and Oppenheimer doesn’t buck the trend despite casting two strong actresses in Emily Blunt and Florence Pugh. Blunt spends the first half thanklessly holding either a baby or a martini before finally getting a handful of strong moments in the third act. It’s obvious that Kitty Oppenheimer is a long-suffering wife to whom motherhood does not come naturally, not helped by being uprooted to the middle of nowhere in the desert with a neurotic, obsessive, and unfaithful husband (rarely is she seen without a drink in hand), but this is all thinly sketched-out and underdeveloped. In the only other significant female role, Florence Pugh gets little to do as Oppenheimer’s emotionally unstable mistress. Arguably the standout in the supporting cast is Robert Downey Jr., looking nothing like Tony Stark behind gray hair, age makeup, and spectacles, and reminding us, now that he’s concluded a long streak of playing little else but Iron Man, that he’s a versatile actor who’s capable of both playing it completely straight and sinking his teeth into a dislikable character. Lewis Strauss, the Salieri to Oppenheimer’s Mozart, orchestrating an elaborate campaign to destroy Oppenheimer’s reputation in vindictive petty revenge for past real and imagined slights, is the closest thing we have to a villain. A cavalcade of more-or-less familiar faces show up in mostly insubstantial walk-on roles, including Rami Malek, Kenneth Branagh, Josh Hartnett, Benny Safdie, Jefferson Hall, Jason Clarke, James D’Arcy, David Dastmalchian, Dane DeHaan, Alden Ehrenreich, Tony Goldwyn, David Krumholtz, Matthew Modine, Gustaf Skarsgard, Tom Conti, Michael Angarano, Jack Quaid, Josh Peck, Alex Wolff, and James Remar. Oscar winners Casey Affleck and Gary Oldman have one scene walk-on roles as Boris Pash, a military intelligence officer suspicious of security leaks at Los Alamos who subjects Oppenheimer to a tense interrogation, and President Truman (of course Oldman is no stranger to Nolan, having played Commissioner Gordon in his Dark Knight trilogy). Oldman doesn’t “become” Harry Truman to the same extent as Winston Churchill in Darkest Hour, but he’s adequate in his cameo appearance.

Oppenheimer demonstrates that Nolan refuses to be pigeonholed as a director, having now done everything from comic book superhero movies to a very unconventional heist thriller to a sci-fi epic to a WWII movie and now an unconventional biopic. Unfortunately, as with Interstellar, there is the sense that Nolan’s ambitious reach sometimes exceeds his grasp, and the self-indulgence that began to show there has only grown further magnified in excessive stylistic flourishes and a time-jumping fragmented narrative structure. Oppenheimer’s weaknesses are partially compensated for by flashes of greatness in the mix, but this is not peak Nolan (for my money, The Dark Knight and Inception represent the director at the top of his game). Oppenheimer represents a frustrating mix of admirable qualities and regrettable choices. It’s technically accomplished and intriguing enough to be worth a look for those interested in the subject matter, but it’s not the next great biopic.

* * 1/2