Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope (1977)

DIRECTOR: George Lucas

CAST: Mark Hamill, Carrie Fisher, Harrison Ford, Alec Guinness, Peter Cushing, Peter Mayhew, Anthony Daniels, Kenny Baker, David Prowse, James Earl Jones (voice)

REVIEW:

Out of the innumerable films that have been released since the late 1800s, not many stand out as trailblazers that changed the entire cinematic landscape, but George Lucas’ Star Wars (the rest of the title wasn’t added until later) is inarguably an example. Not only is it a rousing adventure in its own right, but it revived science fiction as a major movie genre that could attract a large and passionate following, kickstarted a special effects revolution (giving birth to Industrial Light and Magic, the dominant special effects company of the 1980s and 1990s which contributed to everything from Star Trek to Jurassic Park) and arguably gave raise to the modern blockbuster (and things that come with it, like merchandising, mass marketing, and collectible action figure mania). It’s impossible to estimate the full pop culture impact of Star Wars. Even casual fans or virtual neophytes know phrases like “may the Force be with you” or know who Darth Vader is.

Star Wars borrows liberally from various sources, including Westerns, the dogfights of WWII movies, Arthurian legends, Greek mythology, Frank Herbert’s Dune (which features a desert planet, a “Chosen One” protagonist, a scheming Emperor, and a mysterious power known as “The Voice”…sound familiar?), Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces exploring the concept of recurring universal cultural myths and the “hero’s journey”, and Akira Kurosawa’s The Hidden Fortress (C-3PO and R2-D2 were inspired by the characters of Tahei and Matakishi). but the most obvious inspirations are the serialized adventures of Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers that writer-director George Lucas grew up with as a child. If one is being completely honest, Lucas doesn’t strive for much depth or complexity. Unlike its cousin and sometimes rival Star Trek, Star Wars also isn’t—-for the most part—-trying to be deep or philosophical, nor is it trying to be “hard” sci-fi. It’s an unabashedly simple and straightforward—-and not a little cliched—-space opera telling a rousing story of good versus evil (the sides clearly delineated without much in the way of moral ambiguity or gray area) and playing shamelessly on classic mythological tropes such as “The Chosen One”. Dune subverted the “Chosen One” trope and played with moral ambiguity. Star Wars is a fairy tale and a fantasy that paints in broad strokes with light and dark delineated with about as much subtlety as the heroes and villains wearing white and black hats in old-school Westerns (from which it occasionally borrows a page or two). The heroes take nods from Westerns and swashbucklers, and the villains are a cross between Nazis (the Imperial officers with their Fascistic uniforms and clipped accents) and evil sorcerers (Darth Vader). But if subtlety isn’t Lucas’ strong suit (and it decidedly isn’t), he compensates with a vivid imagination, a knack for visual effects wizardry, and an instinctive sense of how to distill the various mythologies he borrows from in a way that blends them into something fresh. Lucas might not be breaking much new narrative ground—-though visual effects were another matter—-but he cannily repackaged familiar themes and tropes for a new audience, throwing them into a blender and churning out something that was uniquely his own.

The story is simple and straightforward. “A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away”, as the opening text informs us, the evil Galactic Empire rules the galaxy, but a band of freedom fighters have stolen the secret plans to its new superweapon the Death Star, a moon-sized battle station powerful enough to destroy an entire planet. The courier of the stolen plans, Princess Leia Organa (Carrie Fisher) is intercepted by the Empire’s ominous enforcer, Darth Vader (David Prowse, voiced by James Earl Jones), but she manages to smuggle the plans into a plucky little droid, R2-D2 (Kenny Baker), who along with his prissy companion C-3PO (Anthony Daniels) jettisons in an escape pod onto the remote desert planet of Tatooine. There, the droids—-and their precious information—-fall into the oblivious hands of Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill), a farmboy longing to see the galaxy and go on an adventure. When Luke discovers Leia’s secret message and seeks the help of the mysterious wizard Obi-Wan Kenobi (Alec Guinness), one of the last of the nearly-extinct monk-like warriors known as the Jedi who use a mysterious power known as The Force, his quest will lead him to the seedy spaceport of Mos Eisley, where they recruit cynical black market smuggler and daredevil pilot Han Solo (Harrison Ford) and his furry co-pilot Chewbacca (Peter Mayhew). Together, our unlikely band of heroes will go on an adventure to rescue Princess Leia and eventually get the plans into the hands of the Rebel Alliance for a dangerous mission to destroy the Death Star.

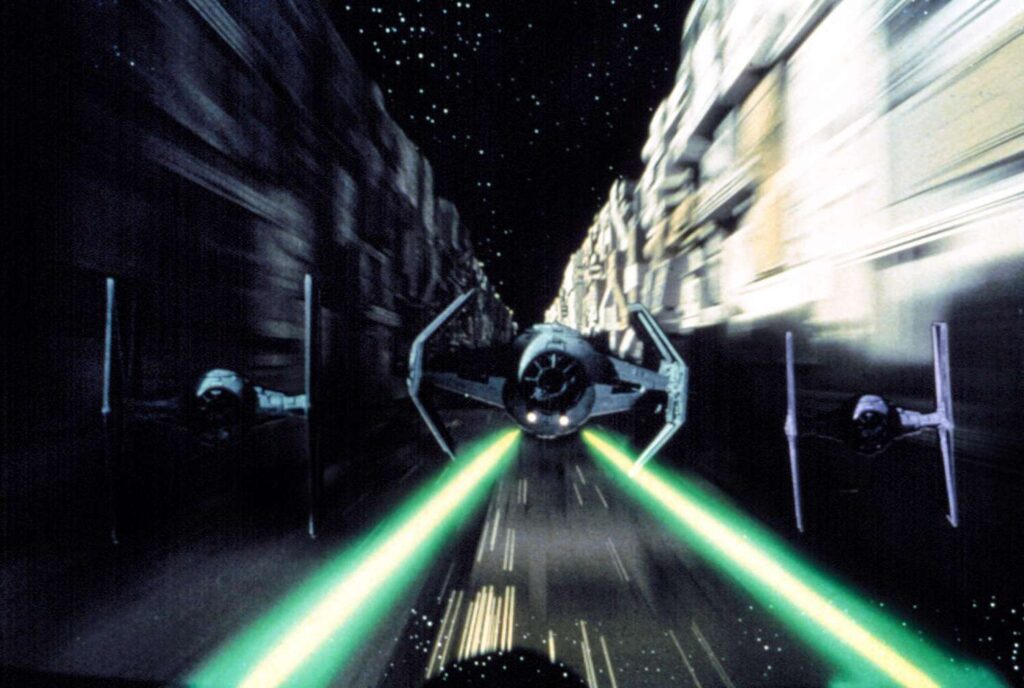

Lucas’ power is in visuals, a medium he understands instinctively. The story might be thin and at times even a little silly, but from the moment the opening text of “a long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away” appears onscreen to John Williams’ iconic grand fanfare, followed by the rousing main theme kicking in (the movie loses some of its power when not on a big theater screen with a surround sound system) as the opening text crawl slides up the screen, followed by the massive Star Destroyer seeming to barrel straight over the audience’s heads, Star Wars has us in its hands. It’s one of the most iconic and instantly rousing openings in movie history. Later, there’s any number of iconic shots, like Luke standing in front of setting twin suns. After opening with a bang, the movie moves a little slow for a while (perhaps a little too much down time on the Lars family’s rather dull “moisture farm”), but later we have the escape from the Death Star, filmed with an affectionate callback to swashbuckling derring-do (and a suspenseful sequence with our heroes trying not to get crushed in a garbage compactor), and the climax with Luke’s bombing run down the Death Star shaft (filmed with an obvious nod to WWII films) while the clock ticks down as the superweapon prepares to fire on the rebel base can still get viewers on the edge of their seats even nearly fifty years later and knowing the movie by heart. A sense of discovery lies around the corner with each scene, from the opening ships in combat, to the robed Jawa scrap scavengers and their Sandcrawler, to the seedy spaceport Mos Eisley and its cantina menagerie of strange aliens. Seen today, some of its visual effects look primitive, but audiences in 1977 had never seen anything like this before. A mere three months prior to its release, the comparatively cheap and unconvincing effects of King Kong had won the special effects Oscar. A New Hope, even in some of its dated moments, was a clear step ahead. And is there a more iconic villain in pop culture history than Darth Vader, with his looming height, billowing black cape, samurai-like face mask, and the booming voice of James Earl Jones?

It’s interesting to note that the movie was originally simply titled Star Wars. The rest—-Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope—-was added later, when Lucas conceived of it as a middle chapter in an ongoing story (the backstory of which would not be brought to the screen until decades later). Despite Lucas’ claims of having the original trilogy planned out all along, some elements here cast doubt on this. It’s hard to believe, for example, that Lucas would have thrown in some of the flirtatious moments between Luke and Leia if SPOILER WARNING he intended all along for them to be brother and sister. And, apart from an ambiguous throwaway line from Luke’s Uncle Owen (Phil Brown) that could be taken a couple different ways, there’s not much to suggest that SPOILER WARNING Luke’s supposedly late father and the archvillain Darth Vader are intended to be one and the same (Leigh Brackett’s original draft of the sequel The Empire Strikes Back, based on Lucas’ own copious notes, seems to bear out that Vader and Anakin were originally two completely separate characters and that this and various other story plot points went through drastic changes during screenwriting). Rewatching A New Hope in hindsight, it’s hard not to feel like some of the series mythos was in its infancy, and Lucas was making up at least some of it as he went along (concept art reveals the story went through some radical rewrites on its journey from page to screen, including Luke being drastically de-aged—-and his name changed from “Starkiller” to Skywalker—-Darth Vader originally having a significantly less important role, and Han originally being an alien). It’s also interesting to note that Darth Vader, the series’ most iconic bad guy—-although he’s a henchman of the as-yet-unseen Emperor, who is only mentioned in passing and whom audiences wouldn’t get their first glimpse of until The Empire Strikes Back—-is in fact a secondary villain here, playing second fiddle and muscle to the Death Star’s frosty administrator Governor Tarkin (Peter Cushing). Unlike its sequels Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi, it can stand on its own as a self-contained story (albeit with a loose end or two) that’s satisfying in itself (something that is not true of Empire Strikes Back, although Empire is a stronger, more accomplished motion picture). Taken in and of itself—-as it existed at the time of its release—-A New Hope is the simple and straightforward stand-alone coming-of-age tale of a farmboy who follows his destiny to rescue a princess and fight an evil empire. Taken in the larger context of the franchise, it’s the fourth chapter of an epic space opera that spans decades in a battle of good versus evil.

While visuals and a breezy sense of adventure and derring-do are among Lucas’ strengths, dialogue and knowing how to handle actors is not. While a number of lines, like Obi-Wan’s urging “use the Force, Luke”, or Darth Vader’s ominously dry-witted “I find your lack of faith disturbing”—-while telekinetically choking a mouthy Imperial officer who scoffs at The Force—-have become famous, the dialogue in general ranges from undistinguished to ham-handed exposition to dopey (Harrison Ford once told Lucas on set, “George, you can type this shit, but you can’t say it”). The acting, whether from then-unknowns Mark Hamill, Carrie Fisher, and Harrison Ford, or established “respected thespians” Alec Guinness and Peter Cushing, is usually no better than adequate. A New Hope relies on the strength of pure narrative, in the most basic storytelling form known to man: the heroic journey, where, like The Wizard of Oz, an Everyman sets out to travel down a road filled with danger, hoping to find treasure or heroism at the end, accompanied by some eccentric but plucky companions (If Luke can be compared to Oz’s Dorothy, R2-D2, C-3PO, and Chewbacca could be compared to the Tin Man, The Scarecrow, and the Cowardly Lion). Lucas’ masterstroke was to take this simple but powerful narrative framework and take it into space, in a galaxy far far away. The characters are not particularly complex, but they’re simple and strongly drawn recognizable archetypes.

At the time, of the series’ “Big Three”, only Harrison Ford was modestly recognizable due to his role in Lucas’ American Graffiti. The other two, Mark Hamill and Carrie Fisher, were unknowns. Their performances aren’t especially accomplished, but what they lack in acting experience they make up for with enthusiasm, and the chemistry and camaraderie among them is quickly apparent. Hamill is possibly the weakest actor, but he makes Luke likable. Carrie Fisher gives Princess Leia a dash of feistiness (and with her iconic hairstyle became the instant subject of many a schoolboy crush). Harrison Ford coasts over occasionally uncertain line deliveries (he made no secret of being uncomfortable with some of Lucas’ corny dialogue) with his charisma and swagger that were already apparent (innate “movie star” qualities that would soon make him the most successful of the three outside of the Star Wars franchise). While the three leads were fresh faces, Lucas threw in a couple of established older “respected thespians” in supporting roles, Alec Guinness as the sage old mentor figure Obi-Wan Kenobi, and the stern-faced Peter Cushing, star of many a Hammer horror flick, as the ruthless Governor Tarkin. Like everyone else in the movie, their performances aren’t exceptional (Guinness was picking up a paycheck, and later made no secret of wearying of all things Star Wars), but they give A New Hope a dash of respectability. While Cushing’s Tarkin is actually the lead villain here, the movie’s most iconic bad guy, Darth Vader, was brought to life through the combined involvement of the costume department, the man in the costume David Prowse, and the commanding tones of James Earl Jones, who deserves a lot of the credit for making Vader as ominous as he is (although here he’s pretty much a glorified enforcer, not yet the series’ “big bad” he would grow into in subsequent installments).

At the time, Star Wars was expected to have a niche following. Even Lucas himself expected it to be a flop, skipping the premiere and going on vacation to Hawaii (where he met another budding visionary, Steven Spielberg, and the two began collaborating on what would become Indiana Jones). Instead, the film shattered all expectations and today, nearly fifty years after its release, A New Hope remains beloved and iconic. While simple and straightforward, it has a breezy infectious sense of joy and innocence that’s easy to get swept up in, combining classic heroic mythology with state-of-the-art (for 1977) visual effects. As familiar and tropey as many of its narrative elements are, Lucas gives them a shiny new sci-fi paint job. Star Wars feels like something fresh and new. Anything I could write about the ways in which Star Wars has changed the movie industry (for better or worse) has already been said by many others. But even setting aside its inestimable cultural impact—-something not easily done—-A New Hope is a rousing and satisfying adventure in its own right.

* * * 1/2