The Da Vinci Code (2006)

DIRECTOR: Ron Howard

CAST:

Tom Hanks, Audrey Tautou, Ian McKellen, Jean Reno, Paul Bettany, Alfred Molina, Jürgen Prochnow

REVIEW:

Ron Howard’s film adaptation of Dan Brown’s novel The Da Vinci Code was preceded by an extraordinary amount of controversy over certain of its plot points which seemed to take on a life of its own, raising the movie and the theological and historical questions it raised into something greater than the film itself. It’s hard to deny that the overblown controversy gained The Da Vinci Code more attention than anything it could have hoped to earn on its own- the saying there is no such thing as bad publicity comes to mind- but the unwarranted firestorm over certain aspects of its content led to it becoming a political and ideological football rather than being judged on its merits as simply no more and no less than an entertaining and interesting film.

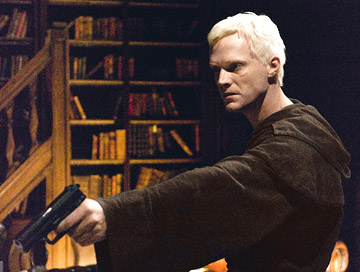

A curator is murdered in the Louvre, and writes strange symbols on himself before he dies. This calls for visiting Harvard symbologist Robert Langdon (Tom Hanks), who is summoned to the crime scene by Captain Fache (Jean Reno) to try to unravel the dead man’s riddle. But Langdon soon learns- with a warning from the enigmatic Sophie Neveu (Audrey Tautou)- that Fache has not brought him for his symbol expertise, but because he believes he is the murderer. Making a narrow escape from the Louvre, Langdon and Neveu discover they may possess the clues to a 2,000-year-old mystery involving warring factions of the Catholic Church and the location of the Holy Grail. They eventually make their way to the mansion of eccentric Grail expert Sir Leigh Teabing (Ian McKellen), who joins their quest. But in their attempts to unlock ancient secrets, they run afoul not only of the pursuing Fache, but Opus Dei, an ultra-conservative faction within the Catholic Church led by the ruthlessly hard-line Bishop Aringarosa (Alfred Molina), who believes that the secret threatens the very survival of the Catholic Church and is determined to safeguard it by any means necessary. To this end he dispatches Silas (Paul Bettany), an albino monk who is willing to eliminate those who threaten to uncover Opus Dei’s secret.

A curator is murdered in the Louvre, and writes strange symbols on himself before he dies. This calls for visiting Harvard symbologist Robert Langdon (Tom Hanks), who is summoned to the crime scene by Captain Fache (Jean Reno) to try to unravel the dead man’s riddle. But Langdon soon learns- with a warning from the enigmatic Sophie Neveu (Audrey Tautou)- that Fache has not brought him for his symbol expertise, but because he believes he is the murderer. Making a narrow escape from the Louvre, Langdon and Neveu discover they may possess the clues to a 2,000-year-old mystery involving warring factions of the Catholic Church and the location of the Holy Grail. They eventually make their way to the mansion of eccentric Grail expert Sir Leigh Teabing (Ian McKellen), who joins their quest. But in their attempts to unlock ancient secrets, they run afoul not only of the pursuing Fache, but Opus Dei, an ultra-conservative faction within the Catholic Church led by the ruthlessly hard-line Bishop Aringarosa (Alfred Molina), who believes that the secret threatens the very survival of the Catholic Church and is determined to safeguard it by any means necessary. To this end he dispatches Silas (Paul Bettany), an albino monk who is willing to eliminate those who threaten to uncover Opus Dei’s secret.

The appeal of The Da Vinci Code is simple- it’s like a treasure hunt. It’s fun to follow Robert and Sophie as they trek across France and England and use clues in paintings and ancient artifacts to uncover one piece of the puzzle which leads to more mystery. In fact, while it’s marketed as a thriller, The Da Vinci Code works better from the treasure hunt angle. Judged from a pure thriller standpoint, there’s too much talking and not enough urgency, too many scenes of characters standing around examining paintings and tombs and giving off-the-cuff history lessons. There are a few tense moments, but we’re not on the edge of our seat. In fact, the thriller plotline is resolved with about half an hour of movie left, and the lengthy epilogue concentrates on the real core of the story- wrapping up the secrets of the past and unveiling final revelations. When it grabs our attention, it’s because we’re intrigued by the unlocking of ancient secrets, not experiencing an adrenaline rush. The Da Vinci Code‘s conclusions might be historically dubious, but the movie- and Dan Brown’s book- does a fascinating job of blending fact, myth, and fiction into an engrossing whole. The revelations onscreen may or may not have any basis in reality, but on its own terms, the movie does a persuasive job of making its case. The shadowy conspiracy and skullduggery provides a cinematic gloss to spice things up.

The appeal of The Da Vinci Code is simple- it’s like a treasure hunt. It’s fun to follow Robert and Sophie as they trek across France and England and use clues in paintings and ancient artifacts to uncover one piece of the puzzle which leads to more mystery. In fact, while it’s marketed as a thriller, The Da Vinci Code works better from the treasure hunt angle. Judged from a pure thriller standpoint, there’s too much talking and not enough urgency, too many scenes of characters standing around examining paintings and tombs and giving off-the-cuff history lessons. There are a few tense moments, but we’re not on the edge of our seat. In fact, the thriller plotline is resolved with about half an hour of movie left, and the lengthy epilogue concentrates on the real core of the story- wrapping up the secrets of the past and unveiling final revelations. When it grabs our attention, it’s because we’re intrigued by the unlocking of ancient secrets, not experiencing an adrenaline rush. The Da Vinci Code‘s conclusions might be historically dubious, but the movie- and Dan Brown’s book- does a fascinating job of blending fact, myth, and fiction into an engrossing whole. The revelations onscreen may or may not have any basis in reality, but on its own terms, the movie does a persuasive job of making its case. The shadowy conspiracy and skullduggery provides a cinematic gloss to spice things up.

The Da Vinci Code really has too much plot to allow much character development, but all of the actors do what they can with their roles, although no one really has enough to work with to achieve three-dimensionality. This isn’t one of Tom Hanks’ most interesting or energetic performances, but he’s a familiar, amiable screen presence, which makes him well-suited to our guide through the film’s mazes and puzzles. Ditto for Audrey Tautou, who manages to lend Sophie a touch of vulnerability. But while the two leads are adequate, it’s the supporting actors who make more impression, none more than Ian McKellen, who steals the show as soon as he appears. McKellen is as delightful as ever, and while Hanks and Tautou are all dour earnestness, his sly humor makes him the only cast member who doesn’t seem to be taking everything deadly seriously. For an example of a wonderful actor making the most of limited material, look no further. Paul Bettany also makes an impression as the tormented Silas, although an albino monk assassin who strips naked and whips himself after each murder to chastise his body for his sins is the kind of character who’s bound to get attention. Bettany’s performance is occasionally chilling, but while he’s hard and unflinching, Silas is also an oddly naive and deluded soul, a misguided pawn of more devious men. The rest of the actors are solid in parts that aren’t much of a stretch- Jean Reno does his stern French policeman thing, and Alfred Molina brings his imposing, somewhat sinister presence to Bishop Aringarosa, while Jürgen Prochnow has basically a cameo as a French banker.

The Da Vinci Code really has too much plot to allow much character development, but all of the actors do what they can with their roles, although no one really has enough to work with to achieve three-dimensionality. This isn’t one of Tom Hanks’ most interesting or energetic performances, but he’s a familiar, amiable screen presence, which makes him well-suited to our guide through the film’s mazes and puzzles. Ditto for Audrey Tautou, who manages to lend Sophie a touch of vulnerability. But while the two leads are adequate, it’s the supporting actors who make more impression, none more than Ian McKellen, who steals the show as soon as he appears. McKellen is as delightful as ever, and while Hanks and Tautou are all dour earnestness, his sly humor makes him the only cast member who doesn’t seem to be taking everything deadly seriously. For an example of a wonderful actor making the most of limited material, look no further. Paul Bettany also makes an impression as the tormented Silas, although an albino monk assassin who strips naked and whips himself after each murder to chastise his body for his sins is the kind of character who’s bound to get attention. Bettany’s performance is occasionally chilling, but while he’s hard and unflinching, Silas is also an oddly naive and deluded soul, a misguided pawn of more devious men. The rest of the actors are solid in parts that aren’t much of a stretch- Jean Reno does his stern French policeman thing, and Alfred Molina brings his imposing, somewhat sinister presence to Bishop Aringarosa, while Jürgen Prochnow has basically a cameo as a French banker.

A review of The Da Vinci Code seems incomplete without addressing the prodigious- and in my opinion unwarranted- amount of controversy the film generated with its ‘blasphemous’ theorizing about certain aspects of Jesus’ life, namely his possibly more-than-platonic relationship with Mary Magdalen, and accusations that the movie is anti-Catholic. It’s undeniable that Opus Dei has reason to be upset about the film’s less-than-flattering depiction of their organization as a shadowy nest of conspirators willing to resort to any means, even murder, to safeguard their deep, dark secrets, but while certain characters express hostile opinions of the Catholic Church, the filmmakers do not seem particularly interested in outright attacking Catholicism. In fact, it is repeatedly stressed that Bishop Aringarosa and his cohorts are a small faction of extremists within the church, and that the Vatican is not party to their morally dubious activities. Sir Leigh Teabing vehemently pushes the belief that Jesus was not divine, but the film does not clearly endorse his stance, and in the end a conversation between Langdon and Sophie addresses the question respectfully and with balance. It is worth noting both that Dan Brown himself describes his story as fiction and does not claim to have written a historical or religious documentary, and that, at least in the opinion of this reviewer, Christianity should hinge more on Jesus’ teachings than his marital status.

A review of The Da Vinci Code seems incomplete without addressing the prodigious- and in my opinion unwarranted- amount of controversy the film generated with its ‘blasphemous’ theorizing about certain aspects of Jesus’ life, namely his possibly more-than-platonic relationship with Mary Magdalen, and accusations that the movie is anti-Catholic. It’s undeniable that Opus Dei has reason to be upset about the film’s less-than-flattering depiction of their organization as a shadowy nest of conspirators willing to resort to any means, even murder, to safeguard their deep, dark secrets, but while certain characters express hostile opinions of the Catholic Church, the filmmakers do not seem particularly interested in outright attacking Catholicism. In fact, it is repeatedly stressed that Bishop Aringarosa and his cohorts are a small faction of extremists within the church, and that the Vatican is not party to their morally dubious activities. Sir Leigh Teabing vehemently pushes the belief that Jesus was not divine, but the film does not clearly endorse his stance, and in the end a conversation between Langdon and Sophie addresses the question respectfully and with balance. It is worth noting both that Dan Brown himself describes his story as fiction and does not claim to have written a historical or religious documentary, and that, at least in the opinion of this reviewer, Christianity should hinge more on Jesus’ teachings than his marital status.

Ron Howard keeps The Da Vinci Code consistently looking good, and brings a stylistic flair to a few scenes which does a nice job of enlivening the historical seminars the characters occasionally lapse into, such as brief reenactments of the Crusades and Langdon’s mental visualizing of the clues he uncovers. The central claim- that Jesus and Mary Magdalen were husband-and-wife- is argued persuasively through a fascinating deconstruction of the Last Supper, partly because the movie puts a lot of effort into making all this seem convincing, and partly because this scene is presided over by Ian McKellen, who can launch into an impromptu, detailed historical lecture and make it sound more animated and compelling than it could have been. The film has a few authentic touches- the French characters speak subtitled French among themselves, for example- and makes good use of its on-location filming in Paris and London, although while it was granted permission to film inside the actual Louvre, Britain’s Westminster Abbey refused the filmmakers admittance on the grounds that the movie was “theologically unsound”, and they instead shot at Lincoln Cathedral in eastern England.

The Da Vinci Code is not a great movie- it’s too talky and lacks the immediacy and tension to hold up purely on its thriller credentials- but it’s compulsively entertaining in the style of the treasure hunt is really is. Those who go into it strictly for the controversy are likely to be disappointed to discover how little of it was warranted, but filmgoers who approach it on its own terms- as entertainment, no more, no less- may become as engrossed in the search for ancient secrets as the characters themselves.

***