K-19: The Widowmaker (2002)

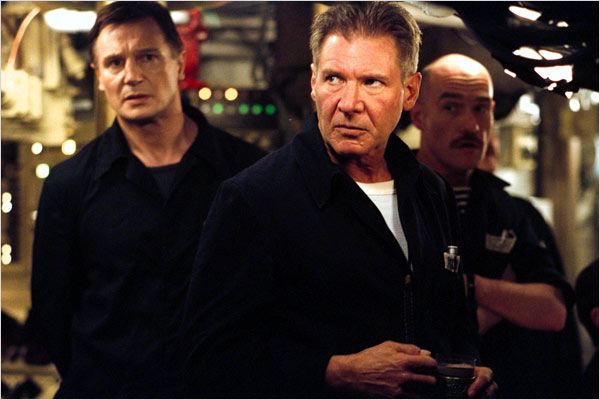

CAST: Harrison Ford, Liam Neeson, Peter Sarsgaard, Donald Sumpter, Ravil Isyanov, Christian Camargo, John Shrapnel, Joss Ackland

REVIEW:

WARNING: THIS REVIEW WILL REVEAL ASPECTS OF THE FILM’S PLOT

Following in the vein of such films as Das Boot and Crimson Tide, K-19: The Widowmaker is a thriller with an epic backdrop of historical conflict unfolding within the claustrophobic confines of a submarine. Kathryn Bigelow’s entry in the submarine genre doesn’t rewrite the book on anything—in fact, at times it’s cobbled together out of cliches, despite being based on an actual incident—but it’s well-made and engaging, and hits the expected points effectively.

In 1961, the Soviet Union dispatches K-19, a nuclear submarine heralded as the “flagship” of the fleet, to be strategically situated off the American seaboard to intimidate the Americans into avoiding any nuclear strike against Moscow with K-19 providing the imminent threat of the annihilation of Washington or New York City. K-19 is touted as the USSR’s most formidable pawn in its game of chicken with the United States, but reality is somewhat less impressive. The sub is plagued by construction problems and mechanical failure before it ever leaves dock. When Captain Mikhail Polenin (Liam Neeson) “fails” a drill (due to faulty equipment which he has no control over), he is demoted and placed under the command of the hard-nosed Captain Alexei Vostrikov (Harrison Ford), who is determined that K-19 will ship out on schedule, mechanical problems be damned. Even before the sub leaves the port, a series of ominous events happen. Several crew members die in construction accidents. The champagne bottle to christen K-19 fails to break against her hull (regarded as a bad luck omen among sailors). Vostrikov fires the reactor officer for drunkenness, and he is replaced by Vadim Radtchenko (Peter Sarsgaard), who is fresh out of the academy and has never been on a sub before. The boat’s doctor is killed in a traffic accident, and his last minute replacement gets seasick. The sub earns its unpromising nickname “The Widowmaker” before it ever sets sail. And once they head out to sea, things don’t look much more promising. Much of the crew remains loyal to their beloved, paternal Polenin and regards Vostrikov as an impostor, and this only increases as Vostrikov pushes the frail ship through relentless and extreme drills that seem unnecessarily dangerous. Tension mounts between Vostrikov and Polenin, and whispers of mutiny grow louder, especially when the men perceive Vostrikov—who married into a politically-connected family—as being more concerned with impressing his Party bosses than with the safety of the ship and her crew. But when the reactor goes critical in the middle of the Atlantic, the crew and its clashing captains will be forced to either pull together or fall apart.

While it opens with the tagline “inspired by actual events” (a somewhat more vague phrase than “based on a true story”, letting the filmmakers play faster and looser with the facts), K-19 leaves no cliche unturned in a greatest hits montage of expected submarine movie plot elements. There is the dive to hull-crushing depths, the headbutting officers, mutinous crewmen, a reactor leak, and an uncontrolled rise to the surface. The plotlines involving Polenin and Vostrikov’s rivalry and mutinous officers recalls Gene Hackman and Denzel Washington’s dynamic in Crimson Tide (complete with a closing scene in which Polenin gives an impassioned testimony in Vostrikov’s defense that echoes a similar scene in the earlier film). The premise of a Soviet submarine near the American seaboard with unclear intentions recalls The Hunt for Red October. The movie isn’t likely to offer any shocking twists and turns (does anyone not have Sarsgaard’s Vadim pegged as a goner the moment we get the goodbye scene with his girlfriend?), but Bigelow does an effective job of ratcheting up the tension, and also throws in at least one striking shot, as the camera moves from the sleeping crew through the thin steel shielding them from the crushing ocean, emphasizing just how fragile their situation is. Things pick up in the second half during the reactor meltdown, and the plot thickens when K-19 discovers it’s being shadowed by an American destroyer, and Vostrikov and Polenin face the decision of steering the half-crippled ship back to base as radiation levels rise rapidly, or surrendering to and accepting the assistance of the Americans…something Vostrikov finds unthinkable. Despite its Cold War setting, this plot aspect may remind some viewers of a far more recent incident, in which the Kursk submarine was lost with all hands in 2000, while Russia refused American and international offers of help. The parallels are a sad reminder that perhaps not that much has changed between 1961 and 2002. And there is a greater danger still: a nuclear meltdown onboard K-19 could destroy the nearby American destroyer, an accident which in the paranoid, tension-fueled Cold War atmosphere of 1961, could be misinterpreted as an act of war. Meanwhile, as K-19 goes out of radio contact near an American ship, Party bigwigs in Moscow begin to smell treason.

There are other intriguing tidbits in throwaway scenes, such as the onboard political commissar (Ravil Isyanov) narrating anti-American propaganda films for the crew, and Polenin’s caustic dinner joke about a Soviet cosmonaut who “was not loyal enough to hold his breath when his life support system failed, so he never existed”, and some nifty details, like red wine slowing the rate of radiation absorption (K-19’s crew naively believes they’re so well-stocked with red wine as a sign of their prestige). Grimmer detail comes when Polenin realizes to his dismay that K-19 is not even equipped with radiation suits (“the warehouse was out”), and the repair teams entering the radiation-filled reactor chamber have nothing but chemical suits (“they might as well be wearing raincoats”, Neeson snarls). Like the German U-Boat crew in Das Boot, we don’t have a problem sympathizing with the Soviets even though at the time they were “the enemy”. Like their WWII German counterparts, the men here may in the grand scheme of things be serving an oppressive dictatorship, but individual seamen are little different the world over. Also, like Crimson Tide, the movie doesn’t one-sidedly make the harder-nosed captain a cut-and-dried “bad guy”. While Vostrikov’s actions may sometimes seem extreme, there are times when we can see he’s an efficient military man testing the crew’s preparedness in ways he deems necessary, and also recognize that Polenin may be overly laidback and paternal, running a ship of ill-prepared men who bumble in emergencies, but there are also times when Vostrikov’s pride seems to get the better of him and many viewers will side with Polenin’s more reasonable and humane attitudes. But in the end, it becomes clear, to the audience and to each other, that each man, in clashing ways, cares for the crew and is doing what he feels is right. There are times when the movie would have us view Vostrikov as the antagonist, but there’s no real “villain” to be found, except in the little-seen Soviet bureaucrats back in Moscow, who push K-19 out to sea unprepared, then hurl ill-informed accusations of treason when things go awry.

Harrison Ford and Liam Neeson are an effectively-cast pair. Like Gene Hackman and Denzel Washington in Crimson Tide, casting the headbutting captains with two authoritative actors keeps the scales balanced (neither dominates the other). Ford is not the most emotive of actors, and has only grown less so with age, but his stern, stoic demeanor suits his part perfectly. Neeson is more emotional and at times, more fiery, but not enough to steal the show from the more subdued Ford. Admittedly it takes a couple minutes to get used to major US and UK stars like Ford and Neeson in Soviet uniforms—Ford can’t seem to make up his mind whether he’s making a half-hearted attempt at a Russian accent or forgetting the whole thing, while Neeson pretty much has one voice and is sticking with it—and if we’re nitpicking, Neeson is far too tall to be a real submarine crewman, but their presences are forceful enough to make physical nitpicks and dubious accents easy to overlook. It’s not the best acting either of them has ever done, but they’re effective in their roles. Among the rest of the crew, the only other individual character to receive more than cursory attention is Peter Sarsgaard, whose inexperienced Vadim is alternately cowardly and heroic. The ever-oily Joss Ackland has a small role as one of the Soviet bureaucrats pushing the mission.

It may surprise some that K-19, something one might think of a “man’s movie” (apart from Vadim’s briefly-seen girlfriend, there is not a woman to be found), was directed by a woman, Kathryn Bigelow, but Bigelow defies stereotypes. Her filmography includes the slightly sci-fi thriller/murder mystery Strange Days, and gritty war docudramas The Hurt Locker and Zero Dark Thirty and is devoid of anything that could be considered a “chick flick”, and she was once married to James Cameron. Bigelow shows she understands how to ratchet up tension when needed, especially in the hull-squeezing dive to extreme depths. However, the mournful orchestral music that plays when the repair team enters the reactor chamber is a bit heavy-handed. Bigelow and her cast and crew haven’t surpassed—or perhaps even equaled—Wolfgang Petersen’s Das Boot or Tony Scott’s Crimson Tide, and K-19 won’t go down as a submarine classic, but it’s a respectable, well-constructed, and engaging entry.

* * *