Spy Game (2001)

CAST: Robert Redford, Brad Pitt, Catherine McCormack, Stephen Dillane, Marianne Jean-Baptiste, Larry Bryggman, David Hemmings, Ken Leung

REVIEW:

Spy Game is a little bit like a John le Carre or Len Deighton story filtered through a Michael Bay/Jerry Bruckheimer (or Tony Scott) visual sensibility, intriguing ideas and twisty-turny plot meeting fast-cutting whizz-bang filming and editing. What results doesn’t always mesh perfectly together, but it contains enough intrigue and fast-paced turns to engage us for an entertaining couple of hours.

We start in 1991, with the Soviet Union collapsing and the United States and China preparing to enter into a trade agreement. But a hiccup comes when a CIA operative, Tom Bishop (Brad Pitt), goes off mission and gets arrested in Beijing while trying to rescue a prisoner (Catherine McCormack) he has a past with. With twenty-four hours until his scheduled execution as a spy, the CIA calls in Bishop’s former boss, Nathan Muir (Robert Redford), a long-standing agent now on his last day before retirement, to fill in the gaps about Bishop’s past and try to explain how and why he got himself into this situation. Thus we jump back to Bishop and Muir’s meeting in Vietnam in the ’70s, and Bishop’s undercover work for Muir in West Germany and Beirut in the ’80s. Meanwhile, in the present, Muir realizes the agency is intending to abandon Bishop to his fate to avoid disrupting the trade deal, and quietly hatches a rescue plan.

The way in which Tony Scott films Spy Game is both an asset and a detriment. On the plus side, there’s no time for boredom, as Scott whisks us along at a frantic pace. On the other hand, there’s not any time for character development beyond perfunctory basics (Muir is the more cynical, ruthless older operative; Bishop is the cocky young hotshot who finds he’s not as hard-nosed as his boss), and the plot whizzes along frenetically enough that some of the details of the various missions threaten to get fuzzy if attention isn’t paid. The jumping back and forth from the past to the present is occasionally a little frustrating, interrupting one story just as we’re getting engrossed in it to pick up another one, but it fulfills its purpose of fleshing out the background of the two men’s connection. Harry Gregson-Williams’ noisy score often threatens to drown out the dialogue, which needs to be heard, especially since, like most spy thrillers not starring James Bond, Spy Game pays more attention to the behind-the-scenes machinations than conventional action. Most of this stuff is more intriguing than car chases and shootouts anyway, as we see the CIA’s willingness to sacrifice an agent when it is convenient to do so. The biggest ethical question the movie poses comes when we see just how far into morally dubious territory Muir (and the agency he worked for) was willing to go to eliminate a terrorist. The situation portrayed onscreen seems even more timely now than it did at the time, and likely provokes more thought in a post 9/11 world than the filmmakers even intended.

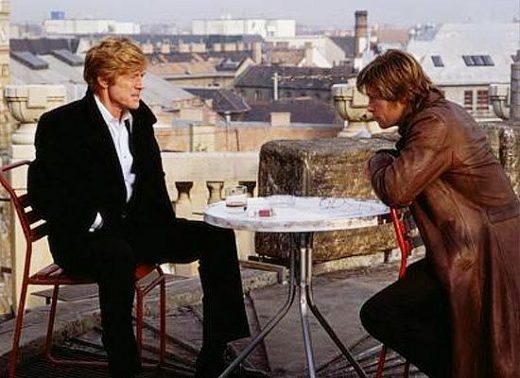

Robert Redford seems at home as the Machiavellian Muir, who lectures Bishop “never risk your life for an asset. if it comes down to you and him, send flowers”. The irony is that Muir, long-accustomed to moving people around like pieces on a chessboard, has problems with following his own advice and hanging Bishop out to dry, going behind his colleagues’ backs to orchestrate an almost one-man rescue scheme, despite that they’re basically doing exactly what Muir himself hammered it into Bishop’s head to do. Muir’s hands are a long way from clean, but Redford imbues him with a tinge of world-weary nobility, a long-standing agent who was “the man who got the job done” by any means necessary but now facing retirement risks his own standing to do what he knows is the right thing. Muir is the only character in the movie who approaches three-dimensionality; Brad Pitt has no problem playing the young hotshot who comes to clash with his boss about how far they should go in the name of completing the mission, but Bishop is more of a type than a fleshed-out character. The movie doesn’t do a good job aging its characters; Muir and Bishop look basically the same in 1991 as they do in 1975. Catherine McCormack has a limited but pivotal role as an aid worker with a checkered past, and Marianne Jean-Baptiste is Muir’s faithful secretary.

Robert Redford seems at home as the Machiavellian Muir, who lectures Bishop “never risk your life for an asset. if it comes down to you and him, send flowers”. The irony is that Muir, long-accustomed to moving people around like pieces on a chessboard, has problems with following his own advice and hanging Bishop out to dry, going behind his colleagues’ backs to orchestrate an almost one-man rescue scheme, despite that they’re basically doing exactly what Muir himself hammered it into Bishop’s head to do. Muir’s hands are a long way from clean, but Redford imbues him with a tinge of world-weary nobility, a long-standing agent who was “the man who got the job done” by any means necessary but now facing retirement risks his own standing to do what he knows is the right thing. Muir is the only character in the movie who approaches three-dimensionality; Brad Pitt has no problem playing the young hotshot who comes to clash with his boss about how far they should go in the name of completing the mission, but Bishop is more of a type than a fleshed-out character. The movie doesn’t do a good job aging its characters; Muir and Bishop look basically the same in 1991 as they do in 1975. Catherine McCormack has a limited but pivotal role as an aid worker with a checkered past, and Marianne Jean-Baptiste is Muir’s faithful secretary.

More than anything else, Redford holds Spy Game up; he has a charismatic enough presence to seem like an entire character among types, and we sympathize with him despite his moral dubiousness because we recognize that he is trying at personal risk to pull one last good thing out of his whole long shady career. Which is not to say Spy Game is a bad or unintelligent thriller. Quite the contrary, it is an entertaining, engrossing ride with twists and turns and a few morally sticky situations, although its frenetic style threatens to distract from the underlying intrigue. Most interesting is following Muir as the uses the same bag of clever tricks from the field to outmaneuver his own CIA colleagues and stage a rescue right under their noses- while spending most of the movie sitting in a room talking to them. Spy Game doesn’t leave the deepest mental impression once it’s gone, but it’s a slickly-crafted piece of intelligent entertainment that’s good for a couple hours of diversion.

* * *