Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace (1999)

DIRECTOR: George Lucas

CAST: Liam Neeson, Ewan McGregor, Natalie Portman, Jake Lloyd, Samuel L. Jackson, Ian McDiarmid, Ahmed Best, Anthony Daniels, Kenny Baker, Pernilla August, Terence Stamp, Ray Park, Frank Oz (voice)

REVIEW:

No release of any movie in recent memory had been anticipated as much as the first of George Lucas’ long-gestating Star Wars prequels. The sixteen year wait also gave Star Wars’ large and passionate—sometimes downright fanatical—fan following plenty of time to build expectations so astronomical that perhaps no movie could have realistically lived up to them. Looking back with the objectivity of years of hindsight, neither blinded by the eye-popping visuals or bitterly disappointed by some of the most banal dialogue in film history and other glaring flaws, it’s possible to see that The Phantom Menace is neither as terrible as its detractors accuse, nor as good as its defenders would argue. It’s also possible to see that, while some of the fan backlash was over-the-top and venomous—a backlash that would eventually turn George Lucas off to all things Star Wars and lead him to sell off the franchise to Disney—some of the blame also lies squarely with Lucas’ own questionable choices, poor judgment, and a self-indulgence that was already starting to rear its head in 1983’s The Return of the Jedi but by 1999 had ballooned as large as Lucas’ ego and controlling tendencies.

We open approximately thirty years before the events of the original Star Wars movie that started them all, 1977’s A New Hope. The pre-Empire Republic and the Jedi Order, long-extinct institutions only spoken of in the original trilogy, are in their heyday. We are introduced to the duo of Jedi Master Qui-Gon Jinn (Liam Neeson) and his young apprentice Obi-Wan Kenobi (Ewan McGregor, stepping into the robes of the late Alec Guinness), who are sent on a diplomatic mission to the planet of Naboo to negotiate an end to the blockade put in place by the greedy and powerful Trade Federation. Unfortunately, there is more going on than meets the eye, and the situation is being orchestrated from behind-the-scenes by the mysterious Sith Lord Darth Sidious. When Qui-Gon and Obi-Wan narrowly escape a trap and make their way to the planet surface, they pick up an unwanted bumbling sidekick, the amphibian Jar Jar Binks (motion capture performance by Ahmed Best) and eventually rescue Queen Amidala (Natalie Portman) from an invasion of battle droids. When their ship is damaged running the blockade, the mismatched group is stranded for a while on the desert planet Tatooine, where they make the acquaintance of a special boy named Anakin Skywalker (Jake Lloyd). Meanwhile, they are being hunted down by Sidious’ fearsome apprentice Darth Maul (Ray Park), who has orders to dispose of the Jedi and capture the queen.

Part of the problem with The Phantom Menace is that it doesn’t seem to be able to make up its mind who it’s being marketed towards. Parts are aggressively aimed at children—most glaringly the bumbling “comic relief” sidekick Jar Jar Binks—while others like the convoluted political intrigue going on in the background are for a more sophisticated audience. Children who laugh at Jar Jar’s antics and are entertained by the eye candy, the podrace, and the climactic battles will get restless during the dry Senate meetings, while adults who recognize and appreciate the significance of what’s really going on in these political scenes will roll their eyes at the juvenile stuff going on too much of the rest of the time. While Jar Jar Binks is impressive on a technical special effects level—a complete CGI character and motion capture performance before those were commonplace—his slapsticky antics quickly wear thin. This underlying structural flaw in the very foundations of the story outline gives rise to many of the other flaws and will continue to infect the prequel trilogy. There’s also some continuity issues. Giving Obi-Wan the master of Qui-Gon Jinn seems to contradict Empire Strikes Back’s reference to Yoda training Obi-Wan. Lucas makes other poor choices as well. Making Anakin Skywalker a precocious child is ill-considered and feels like another concession to the child viewing demographic. Not only does the age difference between Anakin and his future love interest Amidala feel icky—though nothing romantic happens yet, besides his childish crush—but it’s hard to see this boy as the future Darth Vader. Imagine how much better this dynamic could have been with a teenage, edgier Anakin, allowing the possibilities of exploring a budding darker side and romantic tension with Amidala.

If Lucas has never been a master of writing natural dialogue or directing actors, these flaws are magnified in The Phantom Menace, where Lucas has full control as writer-director-producer with no one to rein him in or tell him when something isn’t working. Dialogue has never been the series’ strong suit, but here the dialogue ranges from banal—often consisting of ham-handed exposition delivered by bored actors sounding as if they are reading off cue cards—to cringingly corny (“Yippee!”). Various scenes feel awkwardly stagey, with actors sitting or standing around in elaborate costumes reciting on-the-nose exposition with stilted line deliveries, with Lucas either seeming to not notice how wooden everyone is or not knowing how to coax livelier performances out of them. In A New Hope, the acting wasn’t especially accomplished, but at least the actors felt enthusiastic, and that helped them coast through some clunky dialogue. Never before has Lucas’ poor grasp on how to work with actors been so evident onscreen (Liam Neeson later admitted he “felt like a damn puppet”). In truth, there are actors here—-Liam Neeson, Ewan McGregor, Natalie Portman—-who are probably overall better actors than Mark Hamill and Carrie Fisher, but the characters lack the larger-than-life panache of Luke, Han, and Leia. At times, Lucas’ grasp of interpersonal relationships feels hazy; the parting of Anakin and his mother (Pernilla August) is a little more restrained than one might expect.

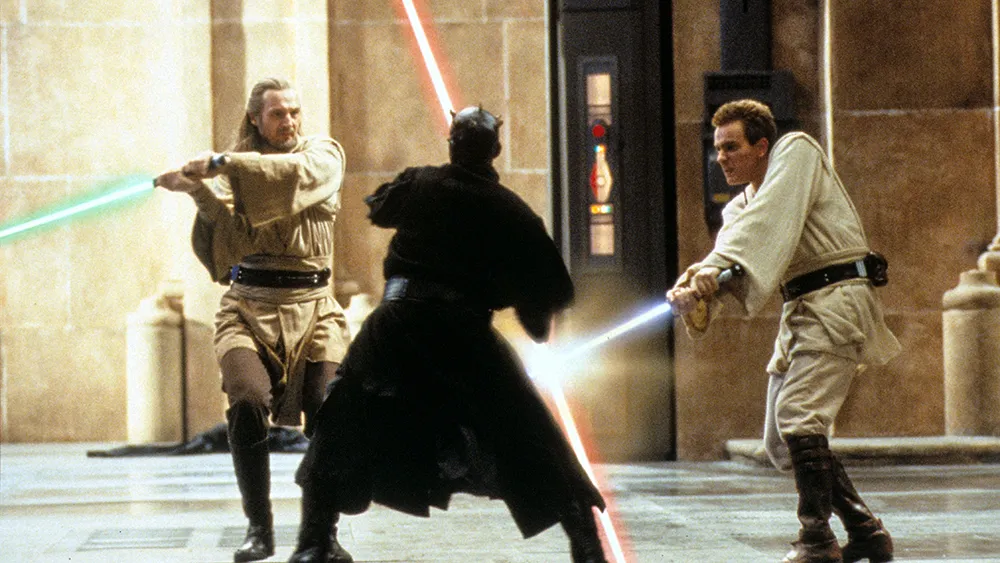

Lucas’ strong suit has always been visuals, and The Phantom Menace delivers on that front, to an eye-popping level. We get new worlds to explore in the lush Naboo and the worldwide metropolis of Coruscant. We visit an underwater kingdom consisting of glowing bubbles and go on an underwater chase against a series of monstrous creatures, each bigger than the last. Lucas frequently cited the limitations of the state of visual effects as a reason why it took so long to bring his prequels to the screen. Like Steven Spielberg and James Cameron, Lucas has always been among a select few filmmakers who consistently pushes the boundaries of special effects. Like A New Hope did in 1977, The Phantom Menace brought things to the screen that 1999 audiences had never seen before. There’s fast-paced space battles, droid armies, intricately-detailed planetscapes, and a menagerie of alien species. The effects were so cutting-edge that, like Jurassic Park, the movie still looks good today, a quarter of a century later. Sometimes The Phantom Menace looks so good and serves up so much eye-popping sensory overload that it’s almost possible to forget about its other limitations. About halfway through, Lucas gives us a lengthy wild desert race with an intentional homage to Ben-Hur. The climax, cutting between four battles—a space battle, a ground battle, Queen Amidala and her soldiers storming the royal palace, and the fast-and-furious three-way lightsaber duel pitting Qui-Gon and Obi-Wan against Darth Maul—is sporadically thrilling, although the effect is marred by Jar Jar’s antics and the unlikely series of events wherein the command ship is singlehandedly destroyed by a precocious child. The lightsaber duel between Qui-Gon/Obi-Wan and Darth Maul is the most ambitious and elaborately choreographed of the entire franchise thus far, with an added level of grandeur from John Williams’ operatic “Duel of the Fates” score. In fact, it’s arguably the strongest singular thing about The Phantom Menace.

Lucas also plays heavily on nostalgia, giving Star Wars fans the first chance in 16 years to see some familiar sights and characters onscreen—along with plenty of new ones. Many of the callbacks are welcome and undeniably affecting to fans of the franchise. In addition to a young Obi-Wan, we have R2-D2 and C-3PO (in a less “completed” form)—again played by their original actors Kenny Baker and Anthony Daniels—Yoda (again voiced by Frank Oz), and a younger pre-emperor Senator Palpatine (Ian McDiarmid, getting to reprise the role without being buried unrecognizably under age makeup as he was sixteen years earlier in Return of the Jedi). Yoda doesn’t look quite right; somehow his puppet here is less convincing and less expressive in 1999 than it was in 1980. The movie also throws in plenty of Easter Eggs: we return to Tatooine, where Jabba the Hutt makes a cameo and we also see Jawas, Banthas, and Tusken Raiders.

As was the case in A New Hope, the acting is no better than adequate, and at least one performance here is more abjectly bad than anyone was in 1977. Unfortunately, that’s Jake Lloyd in the key role of Anakin Skywalker, whose amateurish performance is cringe-worthy. At least some of the blame can likely be laid at the feet of Lucas for not providing the child actor with more of a guiding hand. Natalie Portman falls prey to some of the same problem. For one of Hollywood’s best and brightest up-and-coming young actresses, Portman—while not nearly as glaringly awful as Lloyd frequently is—is often stiff and stilted, not helped by being shoved into an endless revolving door of one elaborate costume after another. All-too-rare are the moments when Portman is given a chance to actually “act”. Liam Neeson manages to coast through with his dignity mostly unscathed; this is hardly among the most impressive performances Neeson has ever given, but he brings a sense of wisdom and calm authority that one would expect from a Jedi Master. Ewan McGregor gives the young Obi-Wan a sense of youthful restless cockiness, yet to achieve the sage wisdom of Alec Guinness. Some recognizable “respected actors” pop up in smaller supporting roles, including Samuel L. Jackson (who publicly practically begged Lucas for a part) as a prominent member of the Jedi Council. Pernilla August does the best she can with the thin role of Anakin’s mother, giving her warmth and dignity despite being saddled with some clunkers (“you can’t stop change, anymore than you can stop the suns from setting”). Terence Stamp plays the Supreme Chancellor of the Republic, but his walk-on role amounts to a cameo (purportedly Stamp was disappointed in his role and felt misled by Lucas about the size of his part). Ian McDiarmid has a few scenes as the slippery Senator Palpatine, maneuvering himself into the Chancellorship with Amidala’s help; when it comes to the identity of the cloaked Sith Lord Darth Sidious, the movie coyly drops hints, but needless to say most Star Wars fans won’t find it much of a mystery. As our more visible villain, Ray Park gets little do to besides stalk around looking fierce until showing off his impressive physical prowess in the climactic lightsaber duel (Park is a stuntman and martial artist). Darth Maul only says a couple lines, and when he does they’re voiced by Peter Serafinowicz, who I guess the filmmakers decided sounded more menacing. The later animated Clone Wars series——set between Episodes II and III—-gave Maul a contrived resurrection of sorts but then managed to do some interesting things with the character, giving him depth and personality he doesn’t have here, but in his live-action appearance, his personality is a black hole.

Somewhere inside The Phantom Menace, there’s a rousing stand-alone space opera trying to get out, but it’s missing the fine-tuning from outside input that lifted Empire Strikes Back to a higher, more mature and accomplished level. Lucas missteps in skewing too hard toward the child demographic and perhaps in thinking he can do everything himself. The Phantom Menace is visually eye-popping, and frequently entertaining, but it’s too flawed to stand as a strong entry in the Star Wars saga.

* * 1/2